China is embroiled in a bilateral trade war with the US but the international legal community is unlikely to panic. Foreign law firms are used to playing a long game there, hears Marialuisa Taddia

THE LOW DOWN

As the US and China embark on a full-scale trade war, much is at stake. Is China’s era of breakneck economic growth set to end? International law firms seem to have much to lose if so – some have spent a generation or more patiently building their presence in the PRC, betting that China’s immense potential can be realised. China’s policymakers traditionally take the ‘long view’, and so must law firms advising on the deal structures that enable everything from global infrastructure projects with Chinese backing to the intellectual property work that accompanies the expansion of China’s consumer economy. An authoritarian state acting as midwife to a free-market economy remains deeply anomalous, but business lawyers have a crucial part to play in trying to make it work.

It was always said that when America sneezed the rest of the world caught a cold; but now economic ill health in China is a bigger risk to global business. Since 2013, the world’s most populous nation has also been its number one trader, ahead of the US.

The rise of China has been meteoric. Four decades of ‘socialist market’ reforms, initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, have transformed it from one of world’s poorest countries to the second-largest economy.

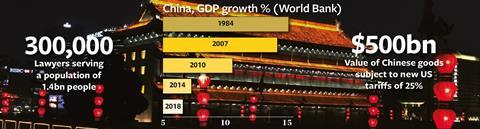

Yet GDP growth was 6.6% last year, the worst performance since 1990. In March Beijing lowered its forecast for 2019 to 6%-6.5%, blaming tariffs imposed by the US. Despite the ‘improved’ outlook for US-China trade tensions, the IMF said in April that China’s output would decline further – from 6.3% this year to 6.1% in 2020 and 5.5% in 2024. This compares with average annual growth of about 10% since 1980. And trade relations with the US have got a lot worse since last month.

The idea that a booming market economy can co-exist long-term with an authoritarian state has always been an uncomfortable notion. Are cracks starting to show?

CMS, which has been supporting clients in China for 40 years, has 60-plus lawyers in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Nick Beckett, managing partner of the firm’s Beijing office, says that although the Chinese economy is slowing, it is still growing significantly faster than the global average (3.3% this year, according to the IMF).

‘China is still viewed by most clients as an important place do to business,’ says Beckett. ‘Due to China’s continued growth, we are seeing a swell in the middle-class population, and it is becoming a much more significant consumer.’ This year China is expected to pass the US as the world’s top retail market, with total sales (boosted by an increase in e-commerce) growing 7.5% to $5.636tn, research by eMarketer shows.

LEGAL TECH: FOUND IN TRANSLATION

Responding to China’s rapidly growing trade and investment flows with the rest of the world is docQbot, a cloud-based automated tool for drafting contracts in Chinese and English.

Robert Lewis, senior international counsel at Zhong Lun, and former managing partner of the Beijing office of Lovells (now Hogan Lovells), is supervising the development of the docQbot templates and user interface. Lewis draws on his 25-plus years’ experience of working on inbound and outbound corporate and commercial transactions in China.

Lewis says the AI platform’s initial offering will be the ‘automated production of high quality, highly customisable bilingual contracts for cross-border and domestic trade, and investment transactions’. It is designed to assist Chinese lawyers in private practice and in-house; Chinese and foreign import-export trading companies and Chinese SMEs; foreign law firms and companies with China-related business; and foreign invested enterprises (FIEs).

‘Users go online, answer a brief series of straightforward commercially-focused questions, taking no more than 15 minutes, and they can then instantaneously create a highly customised bilingual draft contract,’ Lewis explains. ‘Our NDA [non-disclosure agreement] template can create almost 250,000 unique iterations. Other templates can produce literally billions and even trillions of unique iterations. So it is very powerful but still simple enough that non-lawyers can also use it,’ he says.

Market trials started in March with ‘formal’ launch due by end of June. Lewis says there are already more than 1,000 ‘early bird’ users and subscribers in more than a dozen provinces across China.

docQbot is being developed in partnership with HotDocs, a developer of document automation software; China Going Global Think-tank (CGGT), which supports outbound investment by Chinese enterprises under the Belt and Road Initiative, is the majority shareholder, with some additional investment from an undisclosed angel investor.

As the number of consumers grows, CMS has seen more companies in the life sciences, healthcare and TMT sectors seeking commercial advice on entering the market, and, given the significant risks of counterfeiting and infringement, advice on protecting their intellectual property rights. Clients in the region include Japan’s pharma company Takeda, UK’s BP and US media conglomerate CNBC.

China has also embarked on a major programme of reforms to attract foreign investment in key sectors of the economy, Beckett notes, leading to the expansion of other areas of practice such as antitrust, competition and regulatory.

These reforms include the New Foreign Investment law, which increases protections for international investors and their investments in China; a raft of new regulations in the life sciences and healthcare sectors; and new laws on e-commerce and cybersecurity.

Linklaters, which set up its first office in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1998, now has more than 200 lawyers working in China’s main business centres of Shanghai, Beijing and Hong Kong. William Liu, partner and the firm’s China head, says that despite negative media headlines, the consensus is that 2019 will see ‘steady, respectable growth’. He adds: ‘Over the past few years, we have seen many significant changes in China that have created a more open environment for both inbound and outbound investment, and many opportunities for the firm.’

‘COME TO SHANGHAI WITH AN OPEN MIND’

Andrew McGinty (pictured), managing partner of Hogan Lovells’ Shanghai office, has been in China since 1984 – apart from a five-year break to qualify as a solicitor. As an undergraduate student in Mandarin, McGinty spent one year at Fudan University in Shanghai, where he got the China ‘bug’. On graduation, he applied for a British Council scholarship which in 1987 took him to Zhongshan University in Guangzhou, where he studied Chinese criminal law and Cantonese, while also teaching English as a foreign language. After qualifying at Reed Smith (then Richards Butler), in 1995, McGinty moved to Simmons & Simmons in Hong Kong. In 1999, he ‘jumped at the chance’ to set up Linklaters’ Shanghai office, then moved to legacy Lovells in Beijing in 2004 and was promoted to partner a year later. In 2007 he relocated back to Shanghai.

Fluency in Mandarin is ‘critical’ for McGinty’s job: ‘I know that some foreign lawyers and other foreigners in China get by in English only, but I need to be able to participate fully in conference calls where Chinese clients or counter-parties are increasingly demanding and expecting that the calls are in Mandarin. You don’t get all the nuances around tone and emphasis in translation, however good.’

McGinty is enthusiastic about the lifestyle and cultural opportunities in Shanghai. ‘There is literally something for everybody. From sports clubs to wine clubs to running clubs, to bars and restaurants of every possible description… You have great museums, art galleries and exhibitions.’

The building in which McGinty lives is mixed; mostly Chinese with a handful of foreigners.

And what about children? ‘You now have almost an embarrassment of riches in terms of deciding which school to send your children to, including the British International School and Dulwich College. They are very expensive so you need to plan accordingly if, as is largely the case these days, the employer is not picking up the bill. You also have choices in terms of whether you send your children to the international wing of a Chinese school, which was not an option available at the time to my (now grown-up) children.’

Liu points to the Chinese government’s publication last year of a shorter ‘negative list’, which over the next few years will either remove or ease foreign ownership restrictions in certain sectors, such as financial services. There is also the Shanghai-London Stock Connect scheme, which will allow Shanghai-listed companies to raise funds on the UK stock market and vice versa. This is expected to launch shortly.

Liu says: ‘Businesses have a growing need for regulatory compliance support, and our competition practice has been central to helping our clients navigate the evolving legal and regulatory framework in China.’ Other areas are also benefiting: the capital markets team is advising Huatai Securities on its proposed Global Depository Receipts offerings under the Shanghai-London Stock Connect regime.

Linklaters, along with other international law firms, is also seeing instructions related to the multi-billion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This was launched in 2013 by president Xi Jinping to develop China’s links with Asia, Africa and Europe through ports, roads, railways and other hard infrastructure. The magic circle firm’s banking and projects practice has been advising China Development Bank and China Three Gorges, both state-owned, on their BRI-related financing transactions, made possible through the complex deal structures that are a specialism of Linklaters.

In the PRC, Clyde & Co has offices in Beijing, Shanghai and Chongqing with a legal staff of 45; the London-based firm also has an office in the special administrative region of Hong Kong that was set up more than 30 years ago.

Asia managing director Ik Wei Chong says that much of the recent expansion has been driven by outbound work. This has come from state-owned enterprises, which dominate the strategic sectors of the Chinese economy, although Chong says that China’s privately owned enterprises are becoming increasingly active internationally: ‘We have advised on cross-border projects as diverse as water treatment plants in Bangladesh, motorways in Ukraine, and natural resources in Tanzania. We remain very optimistic on the growth potential around BRI, the Greater Bay Area [a scheme to link Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and other cities into an integrated economic and business hub] and Made in China 2025 [to expand high-tech sectors and advanced manufacturing].’

Baker McKenzie was the first international law firm to open an office in mainland China, in 1993, and has since added another in Shanghai, while the firm’s Hong Kong office dates back to 1974. Baker McKenzie now has more than 300 lawyers. Milton Cheng, managing partner of the Hong Kong office, says: ‘While geopolitical uncertainty and greater regulatory scrutiny are causing Chinese outbound M&A deals to shift away from the US, Chinese outbound investment is likely to continue, even if the geographic mix is changing.’

The restriction on practising Chinese law had limited our ability to grow the business in China

Milton Cheng, Baker McKenzie

This is driving the expansion of Bakers’ transactional practices in China, including M&A and private equity, banking and finance, and project finance. Notable recent instructions include: advising Evergrande Health, a PRC company listed on the main board of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, on its acquisition of a 51% stake in National Electric Vehicle Sweden AB for $930m; and a consortium led by Shanghai’s Jin Jiang International Holdings on its purchase of the Radisson Group from Hainan-based HNA Group.

There has also been ‘strong client demand’ for the firm’s dispute resolution services, which include IP, tax, employment and antitrust litigation, international arbitration, compliance and investigations.

Cheng says: ‘Our joint operation allows us to deliver PRC dispute resolution services to multinational clients.’

Foreign law firms are thus benefiting from China’s slow but steady progress towards market liberalisation, which started in 1992 when they were first allowed to open representative offices in mainland China. In April 2015, Bakers was the first legal outfit to take advantage of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone Joint Operation regime (set up in 2013) which allows foreign and Chinese law firms, through a joint operating platform, to advise clients on both international and PRC law while each remains structurally and financially independent, Cheng explains. ‘The restriction on practising Chinese law had limited our ability to grow the business in China.’

Foreign law firms cannot advise on PRC law, make representations in court or employ PRC lawyers unless they give up their PRC practising certificate – but with the new arrangements they can legitimately avoid these restrictions. Bakers’ ‘joint operation’ licence with FenXun Partners allows it to handle matters of PRC and international law ‘seamlessly’. The firm has represented clients before regulators, including the Ministry of Commerce and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, and in Chinese courts. Last year, for example, Bakers successfully represented DreamWorks before the Supreme People’s Court, the highest PRC court, in relation to a domain name litigation in the country.

Other firms have since established joint operation offices with PRC law firms in the Shanghai FTZ: Linklaters with Zhao Sheng Law Firm; Ashurst with Guantao; Holman Fenwick Willan with Wintell & Co; and Hogan Lovells with Fujian Fidelity Law Firm.

Clyde & Co has a ‘joint law venture’ in Chongqing with Westlink Partnership, licensed by the PRC’s Ministry of Justice, that provides ‘seamless onshore and offshore advice as a single entity, including representation in Chinese courts’, Chong says.

Companies are focusing on innovation, improvement in efficiency, and better management. That brings new challenges to the types of services required of lawyers

Michael Wang, Dentons

Other foreign legal outfits have opted for a full merger. Take Australian-Chinese law firm King & Wood Mallesons and Dentons, which merged with Dacheng Law Offices in 2015. Dentons has more than 5,700 lawyers in China, including 1,600 partners. Michael Wang, a senior partner at Dentons in Shanghai, reports a ‘surge’ in outbound investment by Chinese companies, and a consequent increase in demand for legal advice on foreign jurisdictions.

But as China’s economy slows, says Wang, attention is also shifting to ‘the quality of growth, structural adjustment, supply-side reform and further opening up. Companies are focusing on innovation, improvement in efficiency, and better management. That brings new challenges to the types of services required of lawyers’.

Underpinning this evolution is technology. The expansion of the sharing economy and emerging sectors such as internet finance, fintech and smart manufacturing have created new business streams for Dentons in China, according to Wang.

‘MY FAMILY IS ADDICTED TO CHINA’

Robert Lewis (pictured) has worked in China since 1993. In 2011 he joined Zhong Lun, where he is now senior international counsel. Lewis was managing partner of the Beijing office of Lovells (now Hogan Lovells) for nine years before moving to the Beijing office of Shanghai-based AllBright Law Offices in 2010, making him one of the first senior foreign lawyers to switch to a top domestic firm. Prior to joining Hogan Lovells, California-qualified Lewis was Asia general counsel for Nortel Networks and worked in Los Angeles for seven years, including at Sidley Austin.

‘After more than 25 years here, China is home,’ Lewis says. ‘All of my children graduated from the International School of Beijing where they received a world-class education. We love the people, the culture and the food. We have become addicted to the frantic chaos that characterises China’s rapid growth. At the same time, China is an increasingly easy place to live – easier of course for those who speak and read Chinese as I do, but with so many translation tools and bilingual apps available, China is an increasingly comfortable place for non-Chinese speakers as well.’

Lewis is sanguine about the notorious pollution problem in Beijing. ‘We clearly do not love the air pollution but expect that will be remedied in the medium term.’

He says that compared to UK or US firms, Chinese law firms ‘typically have a lighter touch in terms of management, much lower admin-to-fee-earner ratios and much higher levels of partner autonomy and freedom.’

China is a world leader in fintech, including digital payments, online lending and investments. Last year, a Dentons Beijing-based team acted as the Chinese legal counsel of 51 Credit Card in its $129m listing on the main board of the Hong Kong stock exchange. The Hangzhou-based fintech start-up is the largest peer-to-peer lending platform targeting credit card holders in China and the largest online credit card management platform in the country. Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer advised the sponsors.

China is also forging ahead with legal tech developments. According to Thomson Reuters, the number of lawtech patents registered has jumped four-fold in five years, with China filing 51% of the 933 patents in 2018.

Beckett says one of China’s main advantages is its relatively young legal system compared with western economies. The UK and US have far more lawyers per capita than China, which means that law tech is considered less of a threat to jobs. Beckett argues: ‘In China, it is seen as providing essential support to lawyers with extremely large caseloads.’

The number of lawyers has grown rapidly since the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and subsequent rehabilitation of the profession – from 3,000 to over 300,000 in just four decades – but this is still dwarfed by a population of nearly 1.4bn. The PRC government’s focus on turning China into a consumer demand-driven economy has also ‘catalysed entrepreneurship’, Beckett adds.

Tech boom

Bakers’ Cheng points to ‘China’s tech boom, with the nation readily embracing technological advances in robotics and smart tech’. Mobile payments are ubiquitous.

There are now cyber courts handling e-commerce and internet-related claims such as copyright and defamation, online loans and shopping contracts. Cheng says: ‘Chinese courts now offer livestreaming of trials and enable claimants to file cases, submit evidence and resolve disputes online.’ The first specialised internet court, opened in Hangzhou in August 2017, heard about 12,000 cases and closed about 10,600 in its first year of operation. Two additional cyber courts were established in Beijing and Guangzhou in September 2018.

These developments are good examples of how China is ‘leapfrogging’ other legal and judicial systems through technological innovation. ‘We are optimistic that China will become a major player in the legal tech space,’ Cheng says.

However, Robert Lewis, senior international counsel of leading Chinese law firm Zhong Lun, says to date legal tech in China has focused more on big data and less on intelligent knowhow or tech-enabled content. ‘Many players in legal tech in China come from a tech background and not a legal background so are not able to produce high-quality content,’ he says. But this is changing.

Lewis adds that legal technology used in China will be principally ‘homegrown’: ‘NLP [neuro-linguistic programming] for English or other western languages will not work with Chinese or other ideographic languages. Solutions developed to address problems in developed legal markets will not necessarily be applicable in China.’

As ever, then, the sheer scale and potential of China’s economy attracts keen interest, despite the fact that engaging with it is never straightforward. As the Gazette went to press this was demonstrated by the US and China escalating their trade war. Donald Trump ratcheted up the pressure still further by declaring a national emergency to ban technology from ‘foreign adversaries’ and subjecting Chinese telecoms company Huawei to strict controls. Human rights issues are never far below the surface either, as the Gazette’s news pages can testify.

Perhaps what leads advisers to keep faith in China through such ups and downs is a conviction that China’s policymakers intend to take the long view – and that therefore they must do so too.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

The role of international lawyers in the Belt and Road Initiative is the subject of ethical debate, as noted in columnist Jonathan Goldsmith’s 14 May article for the Gazette

6 Readers' comments