With judges striking over radical reforms of the judiciary, tension was in the air as Mexico hosted the International Bar Association’s annual conference. Balancing democracy with the rule of law was a major theme, reports Michael Cross

When democracy clashes with the rule of law, who should come out on top? The standard answer, advanced by many eminent legal thinkers, is ‘neither’: democracy requires the rule of law, and vice versa.

But, speaking at the very end of the week-long conference of the International Bar Association last week, Law Society vice-president Richard Atkinson suggested the conventional answer might work in theory – but that in practice, real-world conflicts between the two must sometimes be resolved by having a winner and a loser.

The conflict had been the dominant theme of a week overshadowed by dramatic developments in the host country, Mexico. On the very day the 4,000 delegates gathered for the opening ceremony in Mexico City, the world’s 11th-largest economy became the first country in the world to make its entire judiciary subject to election by popular vote. Elections for 7,000 judicial posts are due to begin next year.

The judicial reform package provides an archetypal clash between democracy and the rule of law. It was introduced by president Andrés Manuel López Obrador on the back of a convincing election win in June for his leftist Morena party. After admittedly stormy debates, it passed through both houses of Mexico’s parliament. López Obrador’s successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, who takes office next week, has said she will continue her predecessor’s programme of reform under a convincing electoral mandate.

According to the government, the reforms will purge a corrupt and inefficient judiciary in line with popular opinion.

Opponents, apparently including the country’s entire legal establishment, take an understandably different view. Speaking at the IBA conference – which opened with a strong condemnation of the reforms – Professor Lorenzo Córdova Vianello of the Autonomous University of Mexico and a former director of the country’s independent electoral commission described them as a step towards dictatorship.

Politicising the judiciary, he said, is part of López Obrador’s ‘Plan C’, the elimination of all independent constitutional checks on presidential power. As such it marks a slide back to the cult of ‘presidentialism’ which haunted much of independent Mexico’s history. ‘The intention is to do away with democracy and return to autocracy, where all is controlled by the president,’ he said.

'Can you change the whole judiciary without a pause, and public discussion? This was all done in two months'

Lorenzo Córdova Vianello, Autonomous University of Mexico

Challenged by an audience member, Córdova said it is ridiculous to portray the June general election as a referendum on judicial reform. ‘Even if it was, it means that only 54% of voters supported it,’ he said. The very pace of reform should be ringing alarm bells: ‘Can you change the whole judiciary without a pause, and public discussion? This was all done in two months.’

Atkinson suggested that a legitimate judicial reform programme would start from a very different place to that of Mexico’s. ‘Society has to ask itself what does it want from its judges,’ he said. If it wants attributes such as knowledge of the law and independence from the executive, ‘few would come up with direct election as a way to fulfil these criteria’.

Meanwhile, at another session, human rights campaigner Bianca Jagger set out a grim example of where presidentialism in Latin America can lead. Her native Nicaragua, once a beacon of democratic hope, is now a ‘totalitarian state of terror’ under the life-long dictatorship of Manuel Ortega. ‘I am deeply concerned by what is happening in Mexico,’ she told a session on the global refugee crisis. ‘When you see reforms to the judiciary in Mexico, remember what happened in countries like Nicaragua.’

'We are hearing voices, powerful voices, calling for a review of the refugee convention'

Baroness Kennedy of the Shaws

The title of that session, ‘Is the 1951 Refugee Convention a dead duck’, provided a reminder that clashes between democracy and the rule of law are looming much closer to home than in Latin America. Pointing to the rise of anti-immigration political parties across Europe, session chair Baroness Kennedy of the Shaws (Helena Kennedy KC) warned of ‘siren calls to revisit the refugee convention’. Many countries are saying there has to be a restriction on the number of people who should be let in under postwar protections for refugees.

‘We are hearing voices, powerful voices, calling for a review of the convention,’ she said. ‘Some of the nations that were there at the creation of the convention are now the siren voices for change – what are we to do about these voices which will call for reform?’

An obvious response is to publicise the plight of refugees and the moral imperative to take in those in danger. Kennedy highlighted the work of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute in evacuating 102 judges and lawyers from Afghanistan – the effort had to raise more than £3m and took more than a year to place the evacuees. One refugee from the country, the women’s rights campaigner Tamana Paryani, spoke movingly of her experience of imprisonment and torture and the burden of adjusting to life in her new home, Germany.

Emphasising a particular horror of Taliban rule, Kennedy pointed out that ‘there are no women prison officers in Afghanistan’.

However the IBA audience – almost by definition affluent liberal-minded supporters of international legal rules – seemed reluctant to engage with Kennedy’s broader challenge, much less with the ‘siren voices’. The closest anyone came to engaging with the question of reform was Erika Guevara Rosas, Americas director of Amnesty International. She conceded that parts of the 1951 convention were ‘showing signs of age’ amid a global polycrisis in which more than 120 million people have been forced to leave their homes.

Despite this, the refugee convention is a flexible tool which has shown normative power to adapt to new realities, she said. For example, it now protects victims of racial and gender persecution, as well as climate change. ‘It is clear that the convention is not failing – it’s the states which are failing to protect refugees,’ Guevara said. ‘The convention remains as relevant as it was in 1951, the problem is how the state is fulfilling its convention responsibilities.’

And of course it is at the state level that popular – or, as Kennedy strongly emphasised, populist – democracy is most likely to clash with the rule of law.

Selling the benefits of law

An obvious way to head off clashes with popular – or populist – democracy is to persuade the public that it is they who benefit from the rule of law. The legal profession now has a tool to help it in that job. The IBA’s annual conference marked the formal publication of an international study which concludes that the legal profession generates direct economic benefits of $1.6tn a year.

The Impact Report also shows strong correlations between legal activity under the rule of law and economic growth and societal progress as measured against the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Despite this, public recognition of the positive role of lawyers is low: an IBA survey found only 54% of the general public believe that lawyers have a positive economic and social impact. This opinion is shared by 78% of professionals themselves.

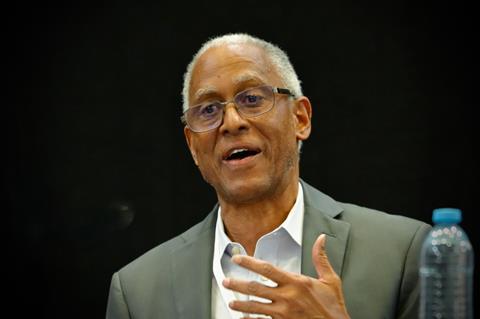

‘The problem is the narrative,’ Tshepo Shabangu (pictured), partner at South Africa firm Spoor & Fisher, told the event. ‘There is not enough information about all the good that lawyers are doing.’

Shabangu cited two South African cases that could help the profession’s image. One was the group action on behalf of gold miners over industrial diseases; the other was the fight for royalties for the family of Solomon Linda, composer of Mbube, which became a worldwide hit as ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’.

Meanwhile Ken Murphy, former director general of the Law Society of Ireland, cited the Irish case of Best v Wellcome over a vaccine which led to brain damage. ‘It was a case of representing the weak against the strong, it showed the legal profession at its best. We have to tell stories and do it with the best means of communication available,’ he said.

One public perception that must be changed, according to Helena Kennedy KC, is the association of lawyers with their clients. ‘We are not hired guns, just there to do what the clients want,’ she said. And lawyers acting for unpopular clients play a crucial point in sustaining the rule of law. ‘We are all human rights lawyers,’ she said. ‘Law is a tapestry and if one part of it is frayed, that reflects on us all.’

Tshepo Shabangu: ‘There is not enough information about all the good that lawyers are doing.’

There are occasions where reference to international legal norms can help settle the argument. Back at the rule of law clash session, Adrian Saunders, a long-serving judge at the Caribbean Court of Justice, recalled a case in Ghana, where an individual tried to challenge the introduction in 1992 of a two-term presidential limit on the ground that it violated the constitution by removing the chance to vote for whoever they wanted.

‘The case was illustrative of the tension between democracy and rule of law and highlights why the rule of law is necessary to temper outcomes of what we consider democracy,’ Saunders said. The challenge was eventually thrown out by a third-instance court partly on the grounds that a presidential two-term limit is internationally widely accepted as a democratic norm. ‘Look to international law as a guide to whatever is happening in your country promotes the rule of law and democracy,’ Saunders said.

Atkinson pointed out that in conflicts with the popular vote, the rule of law starts with the disadvantage of having been developed ‘by the learned few rather than society as a whole’. Democracy, it can be argued, is more reflective of the current mood. Thus ‘if we were discussing it theoretically, then democracy would have to prevail’.

But in practice we cannot always hold up democracy to such a high ideal, Atkinson said. Hence the widely accepted need for a super-majority to initiate constitutional reform. (It was notable that, throughout last week’s conference the Brexit referendum year 2016 was referred to as the start of a ‘global rule of law recession’.) Atkinson stressed that the rule of people must be ‘properly reflected in the electoral system’, launching a brief debate on the merits of proportional representation.

Here, it is clear that different electoral systems will result in different clashes with the rule of law. ‘The fundamental question is how do the people express their will,’ Saunders said. ‘In every society, we have to draw up rules which set out how we demonstrate the real will of the people. The constitution has to set out which institution interprets the constitution.’ Ideally this would be an independent judiciary, he said. ‘What is very frightening is when politicians usurp the power of the judiciary.’

And this is exactly what we are up against, suggested Córdova – citing the Nazi political theorist Carl Schmitt. Populists and authoritarian leaders work by defining friends and enemies of the people – and fighting the enemies. ‘The president is for the people therefore anyone against the president is an enemy of the people.

‘Beware of the concept of the people because if you define that in a homogenous way, you are setting the stage for totalitarianism. Beware someone speaking in the name of the people. Democracy needs the rule of law because it’s the only mechanism to control the abuse of power.’

'Over time, the rule of law will prevail. The people will see that governments which come to power by punching down will find it irresistible to continue to punch down'

Lucy Scott-Moncrieff

Mykola Stetsenko, president of the Ukrainian Bar Association, who faces the unique challenge of attempting to run fair trials of war crime suspects in a country where the war is still going on, put the challenge in another way. ‘Civil society is not the ultimate solution, because they are still people and they may have bias. We need checks on civil society actors,’ he said.

Amid all the talk of impending crisis, former Law Society president Lucy Scott-Moncrieff found grounds for optimism: ‘Over time, the rule of law will prevail. The people will see that governments which come to power by punching down will find it irresistible to continue to punch down. The majority of voters will realise that the rule of law serves their interests.

‘We have to show people they are better off under the rule of law – that it is not a creation of elites who don’t care,’ she said. Such advocacy would seem to be a worthwhile role for the International Bar Association – even if it is itself a body par excellence of elites.

Photographs by Michael Cross

No comments yet