Graphic representation: pictures to access law

During National Pro Bono Week, access to justice should be at the centre of the agenda. Access has to mean openness that ensures more people are able to understand and secure their legal rights. It goes to the root of pro bono, stemming from the Latin pro bono publico: for the public good. And the public need to know what the law is, and how they can determine their entitlements, so that power cannot be exercised in an arbitrary way. That is the rule of law.

A key focus of access to justice must be, understandably, enabling more people to access free or affordable legal representation and advice. However, the focus of this article is slightly different, and flips the emphasis around – how can law be opened up to the public, to work for the public good, when clients may not realise that there is a legal issue in the first place? How can we make law more accessible and transparent, so that communities understand what their legal rights are and can evaluate whether legal help is needed at all?

These questions struck us when we came to work on the Belonging Project. This is a pro bono initiative to raise awareness of the citizenship rights of children and young people, born to Swiss and European Economic Area nationals, living in the UK. Belonging is a set of three communication tools: a comic and a legal leaflet about citizenship, created with PositiveNegatives and the Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens, and an article written in collaboration with Kids in Need of Defense (UK).

This area of law is complex and surprising. For example, being born in the UK does not necessarily mean that you are a British citizen, even if your sibling is. It became clear when we were consulting with young people about the comic that there are many people living in the UK who had assumed that they must be British citizens. They had not realised that there was a legal question there at all, until they came to do something such as ordering a British passport or registering to vote in a general election.

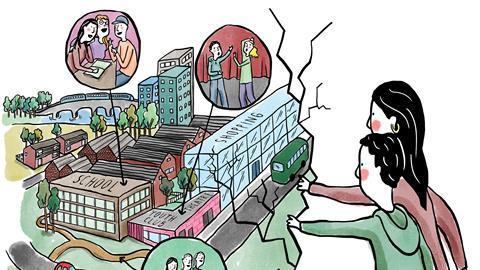

To mirror these experiences, our comic follows Ana, a 17-year-old who wants to change the world. She was born in Spain, and her mum brought her to live in the UK when she was a baby. Since then, she has studied hard, wants to work in politics, and the first step on her journey is to register to vote in the next general election. Her brother and sister were born in England and want to go on a school trip to France, but they need a passport first. They apply for British passports, but only one is accepted. Why? The comic follows the journey of the family and how British citizenship law affects them.

The comic, leaflet and article seek to address that first stage in access to justice – raising awareness of rights so that people know what questions to ask or if they need to take action. It is a springboard to raise questions about legal rights, before someone asks for help.

This brings us to our second point – why a comic? We realised that access to justice is also about breaking down barriers and preconceptions. Some people feel intimidated by, and detached from, the world of law. At the turn of the millennium, that is exactly what the Woolf reforms sought to work against. Legal documents should now be written in plain, clear language. No Latin. They should be able to be read and understood by as many people as possible, not just lawyers. The Woolf reforms heralded a new age of openness and transparency in access to justice. We think that another way of furthering that objective is to use what we would like to call ‘visual law’, using comics, animations and graphic novels to explore complex legal areas.

We wanted to make sure that this vital legal knowledge reached the people who needed it most – where the impact could be devastating if they did not understand their rights to live in the UK, and how best to protect them. Our target audience was children and young people. Taking the form of a comic, we are able to gain a level of readership among our target audience which we would not be able to generate using a standard legal document about nationality law.

Progress is being made by the Home Office to ensure that young people understand their legal rights. The European Children’s Rights Unit at the University of Liverpool, led by Professor Helen Stalford, has consulted with young people about how the European Settlement Scheme (EUSS) can engage with and be understood by those under 18. The consultation showed that 70% of the young people interviewed did not know how to apply for the EUSS; and 28% of the young people consulted were not aware that they are EU citizens and eligible/required to apply for the EUSS.

Considering that failure to apply for the EUSS (where required) could lead to young people being undocumented and therefore living in the UK illegally, this gap in understanding should be taken very seriously. It would leave these children without access to vital education, health and housing services. Stalford and her team are working with the Home Office to put together materials about the EUSS which are aimed at children and young adults. Simply put, adults and children should know what the law is and how it applies to them. That is key to the rule of law.

The comic is different to Stalford’s study but they share important similarities of approach in terms of conveying legal issues in an accessible format. The comic is not seeking to convey every complexity of British citizenship law. It is there to raise questions and provoke discussion among young people and their parents/guardians who might not have considered the issue before. For those who need more detail, there is a leaflet and an article which give a more comprehensive overview. The comic is an innovative way for clients to access legal advice who might have been intimidated by a more classical style of legal document or by attending a legal advice clinic. Visual Contracts is also exploring this area as they aim to make the legal world accessible to everyone by using design-led contracts.

Visual law encompasses human rights, which are co-dependent with the rule of law. As part of a global partnership with Indian social enterprise Barefoot College, Hogan Lovells is helping to increase human rights-related awareness of women from rural India. This project, Drawing on Rights, uses the power of visual images to encourage women to uphold the rule of law as human rights defenders in their local communities. We are working with the Barefoot Enriche team and PositiveNegatives to transform human rights legal research into comics and animations that Barefoot’s semi-literate and illiterate beneficiaries can access to learn about specific rights and the steps they can take to prevent abuse in their communities.

Emily Oliver, managing director of PositiveNegatives, explains: ‘Stories are still too often passed off as childish, rather than one of humanity’s most tried-and-tested ways of understanding the most complex challenges we face in life. A shared passion for humanising law through visual stories, that can be understood by people even with low levels of literacy, is at the heart of the collaboration between Hogan Lovells and PositiveNegatives.’

PositiveNegatives is an award-winning not-for-profit entity that co-creates comics, animations and other stories with people who have deep contextual understanding of some of humanity’s most pressing issues. It has created more than 50 stories with researchers, artists and people with lived experience, unlocking vital research on topics including migration, the environment and mental health. Principally published under creative commons licences, those stories have been submitted to the UK parliament, viewed over 90 million times and used in schools, refugee camps and informal learning around the world.

Through Hogan Lovells Business and Social Enterprise, PositiveNegatives and Hogan Lovells are now collaborating on what is believed to be the world’s first comic contract for safeguarding, which will be freely available for NGOs next year.

Finally, we want to explore film and visual law. Hogan Lovells has co-created Flip the Switch – A Documentary. The film follows the journey of the Barefoot College ‘Solar Mamas’ – women from developing countries who have been trained as solar engineers – and explores key human rights issues such as women’s empowerment, poverty alleviation and climate change. Flip the Switch promotes the importance of shared value partnerships in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, as our partnership with Barefoot College works towards seven of the 17 SDGs.

Flip the Switch has received critical acclaim and to date has been awarded official selection status and winner laurels at 20+ international film festivals, showing how effective visual media can be to involve viewers in a narrative about human rights.

This seems particularly pertinent, just weeks after the BFI Film Festival 2019 opened and Henry Blake’s film, County Lines, has received press attention. The film looks at modern slavery and human trafficking through the lens of a young boy who is drawn into carrying drugs through the county lines by a violent gang. People are using film to highlight marginalised members of our communities, who are sometimes kept invisible. We can use film to convey subtle nuances, the impact of a situation on each character, to shine a light on an issue without trying to offer a simple solution, and that is very powerful.

We should not forget that critical to this idea of visual law and visualising human rights is art as empowerment; art as therapy. Hestia, Hogan Lovells’ charity partner, has launched #ArtIsFreedom, which you may have seen being displayed at London Bridge station on UK Anti-Slavery Day. This year, members of Hestia’s Modern Slavery Response service have used photography to share their stories and begin to recover from their trauma.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of visual law boils down to the reasons why we watch a film, or read a book or comic, in the first place. Is it to learn? To find a moral? Or to feel empathy with a character or situation? There is a place for visual law within those motivations. The lens needs more focus.

This article is written by the pro bono and citizenship team at Hogan Lovells International LLP, with contributions from PositiveNegatives. Hogan Lovells has worked on these visual law initiatives as part of its commitment to access to justice and strengthening the rule of law. Find out more about its work here

No comments yet