To mark LGBTQ+ History Month, Helen Randall recalls the damage Section 28 did to the lives of lawyers and teachers

'When we did our weekly shop together, we drove to a supermarket the other side of London, we used separate trolleys, kept a distance from each other, scared of being seen in such an intimate act by a parent from school. We had two landlines installed at home so that colleagues could ring and not discover with whom we lived.'

This is the account of a lesbian couple who taught in primary schools in London while Section 28 was in force, interviewed for this article. (The new film Blue Jean explores similar issues.)

The context and legacy of Section 28’s prohibition on councils ‘promoting homosexuality and promoting the teaching in school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’ merit reflection as we celebrate LGBTQ+ History Month.

The climate of fear Section 28 created also affected LGBTQ+ lawyers’ careers and personal lives. As a lesbian former colleague who worked at various City firms in the 1980s and 1990s, reminded me: ‘What about the personal cost of Section 28? For example, disguising our partner’s gender, editing our social lives, and never getting too close to our colleagues or clients for fear of being found out?’ She continued: ‘I remember constantly being asked about which club I went to or what I had done over the weekend. I always gave vague answers. As a result, colleagues and clients thought we were standoffish. Inevitably, this wasn’t great for our confidence and, maybe in some people’s cases, career progression.

‘Everyone had two separate lives. Being LGBTQ+ at that time was something everyone I knew hid from employers as Section 28 blighted the public’s view against LGBTQ+ people, so it impacted on lots of things in our lives. This resulted in lots of mental health issues, including depression, loneliness and, sadly for the LGBTQ+ community, even suicides, plus of course the constant fear of being fired.’

In 1967, the Sexual Offences Act introduced a narrow exemption from prosecution for homosexual acts in private between two men, with consent, aged 21 or over. Apart from this one exemption, sexual acts between men continued to be a criminal offence. The act applied only to England and Wales and excluded the armed forces and the merchant navy. Lesbian sex has never been criminalised in England or Wales.

The Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980 then decriminalised homosexual acts between two men over 21 years of age ‘in private’ in Scotland. And in 1982 the European Court of Human Rights struck down Northern Ireland’s continuing criminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults.

Progress reversed

Following those changes in the law, British social attitudes towards same sex relationships began to liberalise until the Aids crisis and the introduction of Section 28.

However, those keen to criminalise any public displays of consensual homosexual activity still had legal means to do so, through the broadly interpreted offences of ‘gross indecency’, ‘procuring’ or ‘soliciting’, covering behaviour most people would not regard as indecent, including gay men kissing or hugging in public or even a hotel room (as that was classed as ‘public’). Some gay men were convicted for gross indecency after being deliberately set up and entrapped by police ‘cottaging’ in public toilets.

After the 1967 act, activities that had not been decriminalised were prosecuted more strictly than before, which led to a steep rise in convictions for so-called ‘gross indecency’. The same acts between consenting heterosexual couples over 16 were completely legal. Prosecutions for relationships between two consenting men over the age of 16 would continue until 2000 when the age of consent was equalised.

Any kind of ‘gross indecency’ conviction for a teacher or social worker would mean they would not pass the required criminal record checks and have to leave their profession. Similarly, a solicitor convicted of gross indecency would probably be sacked and risk losing their practising certificate.

Battleground

1980s London saw a pitched political battle between Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government and the Labour-controlled Greater London Council (GLC) and Inner London Education Authority (ILEA). ILEA applied education policies which were inclusive and progressive for their time.

In 1986, some tabloid newspapers misreported that a Danish mother’s book aimed at opening children’s minds to different family groupings called Jenny lives with Eric and Martin (about a little girl and her two gay dads), was available in the library of an ILEA-run school.

In fact, ILEA had only one copy of the book in a teachers’ centre. However, the media storm sparked intervention by the secretary of state for education and the Conservative government’s proposed introduction of ‘Clause 28’.

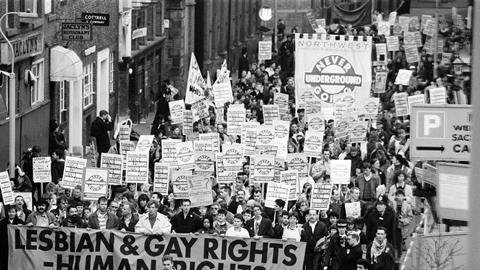

With some trepidation about potential risk of arrest and being struck off (or in my Spanish girlfriend’s case deported), we joined thousands in the widespread public demonstrations against Clause 28 across the UK. But to no avail.

In force

Clause 28 came into force as Section 2A of the Local Government Act 1988 on 24 May 1988. However, the main purpose of the Local Government Act 1988 was to impose a regime of compulsory competitive tendering (called CCT) on local authorities.

After redundancy from a City firm, due to the mid-1990s property crash, I got an in-house local government role. The authority was keen to serve its diverse communities better. I was working on fulfilling and meaningful projects among inclusive colleagues. For the first time, I felt comfortable ‘coming out’ at work. I became a much more confident lawyer as a result.

The council prided itself on excellent in-house services. Hence, we lawyers were instructed to navigate the CCT regime in the 1988 act to prevent forced outsourcing of council services, without breaking the law.

My job also involved drafting contracts for the education and social services departments, and advising that any references to LGBTQ+ inclusive requirements for service users should be disguised in case the council contravened Section 28.

Consulting the Local Government Encyclopaedia to analyse the 1988 act, I was thrilled to see Angela Mason’s name; a former in-house lawyer who later became chief executive of Stonewall.

Stonewall was established in September 1989 to oppose Section 28. It then successfully campaigned to equalise the age of consent, lift the ban on LGB people serving in the military, allow same-sex couples to adopt and ultimately, to repeal Section 28.

Helpline

One evening a week, I moonlighted pro bono for a lesbian and gay legal advice line (GLAD). This was before: gay marriage; the Equality Act; any rights for trans people; repeal of gross indecency; and while Section 28 was in force.

Some GLAD callers were gay and lesbian teachers. They feared they could be disciplined or sacked under Section 28 for ‘bringing their local education authority into disrepute’ if colleagues, parents, governors, or their LEA discovered their sexual orientation. The social backdrop was prevalent vilification of gay and lesbian people as paedophiles (a trope now, some may say, which is reconfigured into transphobia).

A former GLAD co-volunteer recalls: ‘I remember a GLAD client saying as teachers their relationship was secret, so they were not allowed to see their partner who was seriously ill in hospital. Even the partner’s family were not aware of their relationship and so would not let them visit.’

Due to Section 28, teachers were careful to avoid references to LGBTQ+ inclusion, not just in education about sex and relationships but even while celebrating other diversities, such as International Women’s Day or Black History Month. Sadly, there remains the legacy of Section 28 in schools, causing many teachers still to lack confidence and fear openly referring to LGBTQ+ identities. LGBTQ+ inclusive books like Heather has Two Mummies can still be pigeon-holed in school libraries in the ‘issues’ section alongside divorce, adoption and bereavement.

Section 28 was repealed in 2003.

Looking forward

In 2023, we stand on the shoulders of many courageous LGBTQ+ people who fought for our current rights. In the solicitors’ profession, LGBTQ+ inclusion, diversity and equity initiatives are being progressed by the Law Society’s LGBTQ+ committee and other diversity groups, and rolled out in law firms. Clients demand diversity in their legal advisers and, of course, respect for diversity is part of the SRA’s Code.

In the teaching profession, the charity Educate & Celebrate is working to redress the decades of fear created by Section 28 in schools. Their website quotes a parent: ‘All teachers in all schools need [inclusion] training. Thanks so much from a parent whose child has gone through hell with homophobic bullies.’

People who focus on LGBTQ+ identities as being about sex, sexual preference or practices, or genitalia miss the point. Inclusion of LGBTQIA+ and other intersectional identities is about allowing individuals to be respected and to participate contribute fully to society and their chosen professions.

Every young person deserves to be allowed to learn about a world that reflects current society, including the different types of loving and healthy relationships that can exist and the importance of respect. Especially nowadays, given the recent Children Commissioner’s research indicating that 27% of children have accessed pornography online leading to peer-perpetrated sexual violence.

From 2020, Department for Education statutory guidance required all secondary schools to teach Relationships and Sex Education (RES) that is LGBTQ+ inclusive. Primary schools are ‘strongly encouraged (but not required) to teach LGBT content but can choose to teach it in an age-appropriate way’.

This policy does connect families. I was deeply moved when my great niece told me she had done a project for her RES lesson about her ‘lesbian great auntie and Stonewall Housing’ (the specialist LGBTQ+ homelessness charity which I chair).

However, this progress is fragile. The dead hand of Section 28 threatens to re-emerge through calls to change Department for Education guidance.

The lesbian teacher couple, quoted at the start of this article, are married with children. Through working twice as hard and demonstrating impeccable professionalism, they became successful head teachers, each commanding respect across their profession. Having accumulated a huge amount of credibility, they came out, knowing they could be risking their jobs and livelihoods, to colleagues and school governors when their first child was conceived by donor insemination.

The chair and board of governors confirmed their confidence and the schools excelled. The headteachers’ children have grown up as successful, happy, non-judgemental, inclusive people. They are self-confident and they are uniquely themselves. What more could any ‘family relationship’ hope for?

Helen Randall is chair of Stonewall Housing and a consultant at Trowers & Hamlins. She is a member of the Law Society’s LGBTQ+ Solicitors Network Committee.