The low down

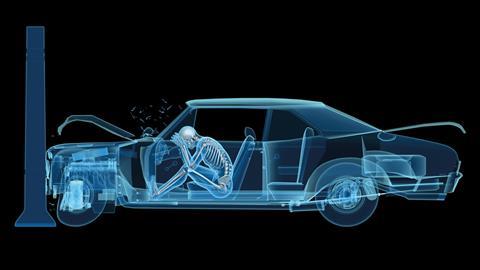

The Official Injury Claim Portal (OICP) is, the Ministry of Justice tells the Gazette, ‘a modern, user-friendly service’. Yet even lawyers say the ministry’s accompanying guide for claimants leaves their ‘head spinning’. Or is the 64-page ‘guidance’, with complex legal concepts featuring from page 1, part of the deterrence to bringing a claim? The process is, after all, arguably designed by and for the insurance sector. It also aims to keep lawyers away from these claims, at least on the claimant side – costs are not recoverable by a winning party. And if the aim is to streamline the process, why is the OICP not integrated with the existing road traffic accident portal? Satellite litigation is predicted.Online technology is reshaping how justice is accessed by consumers and delivered by lawyers. In personal injury, where around 130,000 cases are handled in the civil courts annually, an increasing number of claims are being diverted online and claimants encouraged to bypass lawyers.

Last month saw the launch of the Official Injury Claim Portal (OICP), developed on behalf of the Ministry of Justice by the Motor Insurers’ Bureau for road traffic accident (RTA) claims under £5,000.

The launch of the service is part of the so-called ‘whiplash reforms’ (first introduced by the Civil Liability Act 2018) and coincides with the expansion of the RTA small claims track limit from £1,000 to £5,000. Anyone with an injury claim worth up to £5,000 will now have to use the new portal, and legal costs such as advice, representation and support from a solicitor will no longer be recoverable from the losing side. Instead, claimants will have to pay for legal representation, represent themselves or not bring the claim at all. Whiplash cases cannot now be settled without a medical report. Underpinning these changes are new regulations and civil procedure rules.

The recently published consumer Guide to making a claim runs to 64 pages and has been described by one consumer organisation as ‘legal treacle’. We doubt it will give claimants the clarity they require

Shirley Woolham, Minster Law

The intention is to ‘reduce the unacceptably high number of whiplash claims made each year’ (more than 550,000 in 2019/20). This will allow insurers ‘to cut premiums for millions of drivers’ by ‘passing on the savings [worth £1.2bn] these reforms will create’, the MoJ said in a press statement released on 31 May, when the claims process changed and the new service went live.

‘The new online portal will revolutionise how claims are made, creating a system that is simple and more efficient to use,’ as well as ‘removing the need for expensive lawyers’, the ministry said.

Innovation is slowly but surely transforming practice in this area of law, bringing significant challenges to both practitioners and prospective clients.

Richard Miller, head of justice at the Law Society, says: ‘There are a number of stages where there are some real problems.’ The Society represents practitioners who act for both claimants and defendants, but also has a public interest duty.

New business models

Although it is early days, the new rules on whiplash claims and the launch of the new digital portal are prompting firms to reassess their business approach in this area, says John Cuss, vice-chair of the Law Society’s Civil Litigation Section Committee. The reforms, first announced by chancellor George Osborne (pictured) in 2015 and originally meant to come into force in April 2019, have been repeatedly delayed so many firms are still working on a wait-and-see basis. Others have exited the market (either altogether, or to focus only on the higher end), while some have evolved to adopt new funding models to serve lower-value claims, for example under either conditional fee agreements or damages-based agreements, according to Cuss. A small number of firms are also considering ‘unbundled legal services’ where they would provide a limited legal advice service on aspects of claims such as a complicated self-employed loss of earnings claim or a complex liability situation, Cuss says.

Clyde & Co partner Mark Hemsted says his firm has revised its fee structures to take into account the new types of claim – such as liability-only – created by OICP. It is also developing technologies to integrate into the OICP to complement existing integration to the old portal.

Similarly, Minster Law anticipated the problem of lack of integration between the two online services. Last year Minster launched its digital portal, INK, which integrates the two to create ‘a single, unifying customer journey for claimants,’ says chief executive Shirley Woolham. ‘Regardless of where a customer’s claim starts and ends, or how many times it changes track, the customer journey and digital experience are consistent,’ she says.

Mixed claims

The first problem, which affects claimants but potentially also defendants and their insurers, is how to value ‘mixed’ claims. This is where a claimant has suffered a whiplash injury but also minor injuries not covered by a new fixed compensation tariff for whiplash. This sets out how much can be claimed for an injury, depending on how long it affected the claimant for a period of up to two years.

‘There is nothing in the legislation which says how the courts should deal with something that has both a tariff injury and a non-tariff injury,’ says Miller. ‘From the point of view of claimants, they therefore don’t know what is the right level of compensation for their claim.’ He adds that there is also ‘a real risk’ for defendants, who are often insurers. For example, ‘if they under-settle, they could suffer reputational damage; if they over-settle then they are not complying with their obligations to their shareholders to run the business efficiently,’ he says.

In the run-up to the launch, the profession was still waiting for ‘extensive additional information’, including information on court fees and guidance about making a claim under the new online service. Nigel Teasdale, former president and current executive committee member of the Forum for Insurance Lawyers (FOIL), says: ‘There are challenges for everyone around system integration in a short space of time and training our people to deal with the new process, given this is a pretty seismic shift in how claims will be dealt with in a high volume area’.

It is grossly unfair to expect inexperienced LiPs to go up against defendant insurers who will be very familiar with the portal process

Brett Dixon, APIL

Nevertheless, he says that ‘the main challenge is around valuing additional injuries outside the tariff. This seems to be an issue inevitably requiring test cases accelerated to the Court of Appeal, but practitioners all over the country will be trying to grapple with disputes over those valuations in the meantime’.

David Parkin, deputy director for civil justice and law policy at the MoJ, told a webinar in March that although the OICP ‘does not provide legal advice about what a potential claim is actually worth’, it will be ‘clear’ from the start and throughout how a claimant may value their claims in terms of both whiplash and non-whiplash injuries, and any protocol damages allowed (such as loss of earnings and prescriptions).

For instance, there is ‘signposting’ for claimants to the Judicial College Guidelines as the starting point for valuing their non-whiplash injuries. An MoJ spokesperson tells the Gazette the OICP is ‘a modern, user-friendly service and we have developed further guidance alongside our user-guide and helpline to assist claimants’.

Clyde & Co partner Mark Hemsted says: ‘While the tariff will help litigants in person value the whiplash element of a claim, the guidance within the supporting guide for users of the OICP is likely to be inadequate or cause problems for valuing claims. We expect that some LiPs will value claims using the JC guidelines at the “upper” end of the appropriate brackets, and this might therefore push their own valuation of their claim outside of the OICP. By the same token, some LiPs may undervalue their claims.’

Legal treacle

Qamar Anwar, managing director of First4Lawyers, describes the user guide as a ‘minefield’, while Minster Law’s chief executive Shirley Woolham says: ‘The principle of submitting and managing a claim online is not the central challenge for the vast majority of consumers, but they expect the online experience to be simple, intuitive and easy to use. The recently published consumer Guide to making a claim runs to 64 pages and has been described by one consumer organisation as “legal treacle”. We doubt it will give claimants the clarity they require.

‘The very fact that there has to be a guide for how to use the portal is indicative of what I believe to be the biggest overall challenge of all for litigants in person – the complex and often technical nature of the claims process.’ For LiPs this means understanding and calculating total compensation (general and special damages), representing themselves in the small claims court, proving liability of the third party, instructing medical experts and assessing medical reports.

Miller says: ‘I have to say that, even as a lawyer, the guide to making a claim leaves my head spinning.’ He points to references to ‘non-protocol vehicle costs’ in paragraph 1.1.1, as an example. ‘Presenting people with a complex concept like that on the first page doesn’t feel very user-friendly and inviting to me. I’d also be interested to know whether, after reading pages 13-16, you feel you would be able to value a claim.’ This is one of a number of concerns raised by the Society with the MoJ.

Satellite litigation

Teasdale echoes the views of many when he says that he expects a significant increase in litigation as both claimants and defendants test the new rules and the portal. ‘While litigation overall is likely to reduce over time given the lack of costs [awards] in the system, there will inevitably be litigation around grey areas lacking clarity, and there are quite a lot of grey areas here,’ he says. In addition to how damages will be determined in mixed-injury claims, Teasdale expects litigation over what constitutes ‘exceptional circumstances’ (whereby a judge can award a 20% uplift to the tariff); ‘minor psychological injuries’; and when a claimant representative might ‘reasonably believe’ a claim to be worth more than £5,000.

Gerard Stilliard, Thompsons Solicitors’ head of personal injury strategy, also expects a ‘plethora of satellite litigation so that the courts can set the ground rules’ but he argues that ‘instead there should have been considered decisions and joined-up thinking by government rather than a rush to get this system in place and hang the consequences’.

Stilliard is among those who believe that the system is heavily skewed in favour of defendants and their insurer clients. The main challenges for LiPs include deciding whether, and if so how, to proceed if the insurers deny liability, and how far to challenge them if their offer is too low. They will also have to work out how to gather evidence if liability is denied, decide how to select a medical expert, and value a claim once they get the report, especially if their injuries do not fit neatly into the tariff system, Stilliard explains.

His firm has been acting only for claimants for the last 100 years and ‘long experience teaches us that it is in insurers’ DNA to pursue unjustified denials of liability, to delay and obstruct’, Stilliard says. This is a system the government has allowed to be designed by and for insurers, meaning ‘there is little by way of sanction for poor behaviour. That will inevitably lead to justice being denied’.

LiPs, he continues, ‘will either be forced to drop claims or to take their chances in a David-and-Goliath conflict against hugely well-resourced insurers in a county court system which is already creaking to the point of collapse after a decade of cuts. It is a system that may be pushed over the edge with an influx of new RTA small claims’.

In addition, ‘insurers are already lining up their excuses for not delivering on premium savings which, along with a drop in cold-calling (which we also doubt will ever happen), was the carrot held out by both insurers and government throughout the passage of the Civil Justice Bill through parliament’, Stilliard concludes.

Anwar has concerns ‘there will be a lot of pushing back by defendants, with insurers saying to claimants “we’ll offer you a £240 payout today, or you can try and go through the system, try and navigate it yourself and end up with this same £240, or maybe less”. Claimants will be none the wiser and possibly intimidated by the legal aspect, and with no knowledge of what their injury is really worth, may take the offer for fear of the complicated process that lies ahead.’

Removing legal advice

Brett Dixon, vice-president of the Association of Personal Injury Lawyers, says: ‘The issue with this new system all comes down to a lack of legal advice in what is a complex area. It is grossly unfair to expect inexperienced LiPs to go up against defendant insurers who will be very familiar with the portal process.’ There are also other issues still not understood, according to Dixon, including before-the-event insurance, and what support the third sector could provide to claimants. ‘What is clear is that the standard of service the injured person will be able to access is going to decrease,’ he says.

The lack of ‘data portability’ between the new online service and the original Claims Portal (often interchangeably called ‘RTA Portal’) is another key issue raised by the Society that remains unsolved. What if a claimant starts a claim in the OICP that turns out to be worth more than £5,000 and they have to move to the old online service? The Claims Portal, used by solicitors for claims up to £25,000, was first introduced in 2010 and extended in 2013 to include employers’ liability and public liability claims. (The government did not increase the small claims limit in EL and PL, so for now they fall outside the OIPC).

Miller says: ‘The MoJ has said that this will be provided in PDF format, which means the claimant will have to re-enter the data in the other portal, rather than being able to upload the information.’

Jayne Bowman, head of civil justice and law policy at the MoJ, said at the March webinar that there are currently ‘no plans’ to link the OICP to the portal for handling higher-value claims, adding that the use of the latter is likely to diminish. In the launch press release the MoJ said that ‘it is anticipated that the majority of road traffic accident claims will use the [OICP] in the future’.

‘It would have been far better for the two systems to be integrated,’ Stilliard says. ‘The fact that they were not and that the government sees the existing portal dwindling away makes clear what the agenda is here. This is not about providing an easy system for claimants to submit genuine claims, it’s about hoping that those claims simply go away.’

In a system with few if any recoverable costs, it is going to be time-consuming to resubmit claims which drop out of the OICP; and with multiple submissions comes any number of unwanted outcomes such as discrepancies between claims, double-claiming, fraud and conflicting judgments, according to Stilliard.

Tale of two portals

Hemsted points to a ‘lack of consistency’ across the two services. Whereas the old portal allows credit hire claims within it, the OICP specifically excludes them. And while one of the stated benefits of the new OICP is that LiPs and other non-solicitors (for example claims management companies) can progress claims without legal representation, this is not possible through the old portal.

Notable, and arguably confusing for consumers, is that only the new service is called ‘official’ despite the fact that both portals have been created under the auspices of the MoJ.

The changes do not apply to claims involving children. But this means that if, say, two siblings aged 17 and 19 got hurt in the same accident and their injuries were identical (and their claims worth less than £5,000), these would be handled by two separate portals. Miller says: ‘You might think that in a situation where you have got a single accident with multiple claimants you just have a single process to deal with all of them, but you will have to make two separate claims into completely different systems with two completely different sets of rules, and the two are not linked.’

There are similar concerns for defendant representatives. Teasdale says: ‘While I wouldn’t go as far as saying that the two services should be combined, at the very least they should sit under one umbrella where they can talk to each other and perhaps with a single point of entry. That would also assist with data collation.

‘Additionally, in the future having a system that can then link directly with the online court service where dispute resolution is required would make the process much more digital friendly.’

The OICP is a pre-court process which is designed to help claimants to follow the pre-action protocol and settle before a court claim is started.

If a claimant then decides to issue court proceedings to resolve the issue, the court process is currently almost entirely paper-based, and Miller says there is ‘no link whatsoever between the two’ – claimants will have to re-submit their claim. Miller adds: ‘There is going to be an awful lot of burden on the injured person in having to constantly keep re-entering all this information into a different system and there is also a much greater risk of mistakes.’

The future

Firms working at the lower-value end of the personal injury RTA market may benefit from revising business models to adapt to the changes, the Society has advised.

The small claims limit for vulnerable road users (VRUs) such as cyclists, motorcyclists and pedestrians has not increased and costs are still recoverable. This means that ‘it will still be possible for lawyers to advise VRUs cost-effectively, but we don’t necessarily know what sort of size market that is going to be and therefore whether it will be economically viable’, notes Miller.

Because children and protected parties are not part of the new small claims limit either, Dixon notes, ‘they are, in fact, in a better position than before in relation to legal help, but not damages [because they are subject to the new whiplash tariff system]. People who are bankrupt, personal representatives of estates, and foreign vehicle defendants are also not included in the small claims increase’.

Hudgell Solicitors’ John Cuss, vice-chair of the Law Society’s Civil Litigation Section Committee, says firms are weighing up the pros and cons and not jumping the gun: ‘Ultimately, the question everyone is asking is: “Can we really afford to turn away these claims at the outset?” It is very difficult to know with any degree of certainty at the outset of the claim in the initial days or weeks after the accident how much compensation a claim will eventually be worth.’ What could first appear to be an obvious small claim may later become a ‘fast track’ or even a ‘multi-track’ value case.

The whiplash reforms and underpinning digital portal are clearly a mixed bag for claimant and defendant solicitors, and the industry generally. Teasdale says: ‘Even if we see a reduction in claims brought, it won’t be anything we aren’t used to, having coped with a significant reduction in claims since Covid.

‘The potential increase in claims management companies has long been talked about. While this may be the case pre-litigation, conducting litigation remains a reserved legal activity and so those CMCs will have to instruct a law firm.’

One upside of the portal is that it will generate ‘a significant amount of data’ to understand user behaviour and satisfaction, and the performance of the service, Parkin told the March MoJ webinar. This will be useful evidence for any ‘further reforms if parts of the new services aren’t quite working’. The MoJ, he said, is committed to publishing helpful data, but final decisions are yet to be taken on the data to be shared.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet