Imprisonment for public protection swiftly became a policy without supporters. Abolished in 2012, why are so many prisoners still caught in its clutches? Catherine Baksi reports

The low down

Sentences of imprisonment for public protection were abolished in 2012 by the coalition government, which called them ‘not defensible’. Trapping prisoners in jail with no end date and no hope of getting out, they have been heavily criticised. The Labour home secretary who introduced them has admitted that they were a ‘disaster’. Yet nearly a decade after such sentences were scrapped, hundreds of IPP prisoners remain incarcerated, many after completing the minimum term imposed by judges. And rising numbers of released prisoners have been recalled to prison, often for minor breaches, prompting calls for further reform.

Pressure is mounting on the government to remedy an injustice branded by former Supreme Court justice Lord Brown as the ‘single greatest stain on our criminal justice system’.

The former lord chief justice, Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, told the House of Commons justice committee last December that all prisoners serving indeterminate sentences of imprisonment for public protection – so-called IPP sentences – should be re-sentenced.

Lord Thomas said: ‘You need to fix the immediate problem quite quickly by some sort of rough and ready justice; first, to deal with those who are still in prison when you have gone beyond the maximum that they could have for a determinate sentence, and, secondly, to deal with those on licence.’

Because ‘something has gone wrong’, said Thomas, this requires looking at the ‘injustice’ that has been done to IPP prisoners, the majority of whom were not dangerous, yet in respect of whom imprisonment has ‘made worse and less susceptible to release than had they been given a determinate sentence’.

In the same week, peers on both sides of the Lords called for an amendment to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill to allow for the release of IPP prisoners who had served more than their tariff sentence unless they posed a risk to the public, and to reduce the time they spend on licence. Tory peer and former solicitor general Lord Garnier QC told his colleagues: ‘This obscenity must now end.’

'IPP sentences are a form of modern-day torture, fuelled by a constant sense of anxiety, hopelessness and strong feelings of injustice'

Baroness Burt of Solihull

Fellow barrister and cross-bencher Lord Pannick, meanwhile, noted that the government ‘have had years to think about the options’. He asked what it was going to do to ‘address a manifest injustice’.

Liberal Democrat peer and former assistant prison governor, Baroness Burt of Solihull, also weighed in. She described the sentences as ‘a form of modern-day torture, fuelled by a constant sense of anxiety, hopelessness and strong feelings of injustice and alienation from the state’.

IPP sentences were introduced by the Labour government through the Criminal Justice Act 2003, for offences committed on or after 4 April 2005. They were designed to ensure that dangerous, violent and sex offenders, whose crimes were not so serious as to merit a life sentence, stayed in prison for as long as they presented a risk to society.

Punitive element

Like a life sentence, IPP had a tariff or punitive element, which had to be served before the individual could have their case reviewed by the Parole Board. IPP prisoners could only be released if the board was satisfied that they had addressed their offending behaviour and were no longer a risk to society.

But it is difficult for prisoners to prove such a negative, argues Aston Luff, a solicitor at Hodge Jones & Allen. Luff represented the family of Tommy Nicol, who took his own life after spending six years in prison on an IPP sentence.

As originally drafted, there was no minimum requirement for the length of the tariff and IPP sentences were given to less serious offenders who had very short tariffs – in one case, just 28 days.

Dean Kingham, a prison and public law solicitor at the London law firm Reece Thomas Watson, explains that the overcrowded prison system being ‘starved of resources’ meant prisoners were unable to access the rehabilitative programmes to help demonstrate that they were no longer a risk. As a result, they were kept in prison for months and years after the tariff had expired.

By December 2007, when there were 3,700 IPP prisoners, it was estimated that 13% were over tariff. This led the Court of Appeal to rule that the secretary of state had acted unlawfully, and that there had been ‘a systemic failure to put in place the resources necessary to implement the scheme of rehabilitation necessary to enable the relevant provisions of the 2003 act to function as intended’.

According to the House of Commons justice committee, which is conducting an inquiry into the problems caused by IPP, some 96% of those still in prison have completed their minimum term; many have served two or three times longer than their minimum term; and over 500 have been held in prison for over 10 years longer than the tariff they were given.

Even when an IPP prisoner is released, explains Luff, they are subject to an indefinite licence period. For the rest of their lives, they are potentially liable to being recalled for minor breaches of their licence.

'Many of those released continue to suffer high levels of anxiety and stress as a result of the awareness that they may be recalled by probation without notice at any moment'

Aston Luff, Hodge Jones & Allen

Andrew Sperling, a solicitor at Tuckers, criticises the process – administrative rather than judicial – which makes recall ‘too easy’. Requests, he says, are ‘almost never refused’ and are triggered for non offence-related breaches, such as missing probation appointments, returning late to approved premises, or for behaviour which ‘would not remotely reach the criminal or custodial threshold in other circumstances’.

Once recalled, it is difficult to be released again and, says Luff, prisoners again have to wait for a hearing to prove to the Parole Board that they are safe to be let out once more.

‘Many of those released therefore continue to suffer high levels of anxiety and stress as a result of the awareness that they may be recalled by probation without notice at any moment, irrespective of their efforts to comply with the licence conditions,’ he says.

While they can apply for their licence to be cancelled after being out for 10 years, Sperling points out that only about 70 have successfully done so.

In the wake of widespread criticism, in 2008 the Labour government reformed the regime to introduce a ‘seriousness threshold’ that had to be satisfied before the court could impose an IPP sentence, which meant prisoners generally had to be given a determinate sentence of at least two years.

Yet the same problems persisted. In 2012, three prisoners who were subject to IPP sentences went to the European Court of Human Rights, in James, Wells and Lee v UK.

The court held that the failure to make appropriate provision for rehabilitation services while the men were in prison breached their rights under Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects the individual from arbitrary detention.

Inheriting the ‘very serious problem’ of IPP prisoners, which the prisons minister Crispin Blunt in June 2010 labelled as ‘not defensible’, the coalition government finally abolished the sentences in the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012. They were replaced with mandatory life sentences for second serious offences and new extended sentences. But the change was not made retrospective and did not affect the position of existing prisoners serving IPP sentences.

In 2005, the Labour government had anticipated that the regime would be used for around 900 offenders, but IPP sentences were given to 8,711 people. When they were abolished, there were still over 6,000 IPP prisoners in custody.

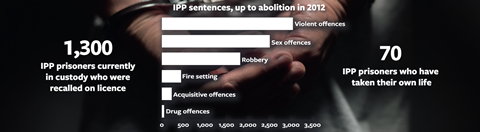

According to figures from UNGRIPP, a group that supports prisoners and their families and campaigns for reform, IPP sentences were given for 107 offences – 3,045 (35%) for violent offences, 2,508 (27.8%) for sex offences, as well as 1,822 (21.6%) for robbery and 448 (5.1%) for fire setting offences. A further 232 (2.7%) were given for acquisitive offences and 11 (0.1%) for drug offences.

Of those sentenced 249 (2.9%) were women and 326 (3.7%) were children, including a boy aged 10-11.

Swallowed by the system

‘S’ was convicted of robbery and sentenced in November 2005. The victims were his parents, who have continued to support him.

His minimum term expired in August 2007. He was moved between 23 different prisons between 2007 and 2014, and in almost all of them he was detained in segregation units.

In 2014 S was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, or autism spectrum disorder. Features of his condition included a heightened sensitivity to large numbers of people, noise and commotion.

Following his diagnosis, he was transferred between three different hospital units before being returned to prison in 2017.

After four years of delays, a Parole Board hearing in July 2021 directed his release on licence to a probation hostel, noting that the staff should be aware of his needs and that there should be transition work to prepare him for the move.

After serving more than 14 years longer than his minimum term, S was released on 6 September. But only five days later, he was recalled to prison because he had failed to return to the hostel for his 10am sign-in and had told staff he had a grievance with another resident.

S now faces the prospect of waiting between six and 12 months for his continued detention to be reviewed. If he is able to persuade a new panel to release him again, he will remain on licence for several years and the likelihood that he will be recalled again is very high.

Nearly a decade after IPP sentences were scrapped, the latest figures from the Ministry of Justice reveal that on 30 September last year, there were still 1,661 IPP prisoners who had never been released, while a further 1,300 have been recalled on licence.

Lord Blunkett, the Labour home secretary who was the architect of the sentences, has expressed regret about the way they were used, telling BBC Radio 4’s World at One recently that the number of people still in prison ‘weighs heavily’ on him.

Giving evidence to the justice committee, which has received more than 500 written submissions to its inquiry, Blunkett said that if he had his time again, he would still have introduced them in order to protect the public.

But he admitted that the bill should have ‘laid down explicitly’ that there had to be ‘a very substantial determinate sentence before the IPP could be applied’.

He also admitted that funding had not been provided for rehabilitation and said the bill should ‘have said explicitly that the measures could not be brought in until the funding had been provided to an adequate level by the Treasury, to ensure that those therapies and courses existed’.

To make matters worse, the number of people being recalled to prison under the terms of IPP has risen significantly in the last five years, increasing by 100%. Calling for ‘urgent measures’ to deal with this, Blunkett told the committee: ‘We are in a really dangerous moment with 1,700 still in prison and 1,300 who have been recalled on licence, with the number being recalled on licence estimated to exceed within a very short period of time those who are still in prison on IPP.’

Lack of resources for rehabilitation and delays in parole hearings mean that IPP prisoners continue to languish in jails. The harmful impact on their mental health and wellbeing has been documented in numerous reports from the Howard League for Penal Reform, the Prison Reform Trust and Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons.

IPP prisoners experience high levels of anxiety and have rates of self-harm and suicide that are significantly higher than other categories of prisoner, including those with life sentences.

The impact of the sentences on prisoners and their families has been devastating, says Luff, stating: ‘I am yet to talk to someone subject to an IPP sentence who does not have a story that is gut-wrenching.’

Such sentences, says Sperling, disproportionately disadvantage neurodiverse prisoners, for example those with autism spectrum disorder or learning difficulties. They may find it very difficult to navigate pathways to release and therefore serve more time in custody than neurotypical prisoners.

In a written submission to the justice committee, UNGRIPP says the worst element is the ‘indeterminate’ nature of the sentence, which resembles a ‘living death sentence’.

It added that prisoners and their families have described that element of the sentence using words like inhumane, torture, torment, horror and despair.

The lack of a release date, says Kingham, is ‘incredibly hard for many to process’ and has resulted in ‘significant hopelessness’ which often leads to negative behaviour.

The clamour for reform has been backed by former justice secretaries Ken Clarke and Michael Gove, as well as probation and prison chiefs.

Giving the annual Longford Lecture in 2016, under the title ‘What’s really criminal about our justice system?’, Gove proposed that the government should use the power of executive clemency to release those IPP prisoners who have been in prison for much longer than their tariff.

Backing Lord Thomas’s proposal, Kingham says the government should re-sentence all the remaining IPPs to determinate sentences with fixed release dates, rather than leaving the release decision to the Parole Board.

Another option, says Luff, would be to revise the test that requires the prisoner to show that they are no longer a risk, putting the onus on the Parole Board to prove that they remain so. The LASPO act already provides for this change, which was backed by Nick Hardwick, the former chairman of the Parole Board.

Campaigners are also calling for reform or removal of the licence conditions and support for IPP prisoners and their families.

In evidence to the justice committee, Kit Malthouse, the minister for crime and policing, stressed that the government’s first consideration was public protection. He insisted that existing measures were working to reduce the number of IPP prisoners in custody, though he conceded that it ‘may well be’ that some are never released.

An MoJ spokeswoman told the Gazette that the number of IPP prisoners has fallen by two-thirds since 2012. She said: ‘We are helping those still in custody progress towards release, but as a judge deemed them to be a high risk to the public, the independent Parole Board must decide if they are safe to leave prison.’

She said ministers have no plans to retrospectively alter these sentences, but said the IPP Action Plan is regularly refreshed, to ensure it addresses the challenges faced by offenders serving them.

The justice committee hopes to publish the report on its inquiry early this year. Whether its recommendations will be acted upon remains to be seen.

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist

2 Readers' comments