Insecure tenancies and poor living conditions have pushed the plight of the UK’s growing army of renters up the political agenda. But in England ministers continue to fudge and prevaricate on much-needed reform, reports Maria Shahid

The low down

Problems in the private rented sector regularly hit the headlines. Rents have soared as home ownership figures have plummeted, meaning that more households fear summary ‘no-fault’ eviction. The response in England is the Renters Reform Bill, designed to improve tenant security. But is this legislation the latest of many false dawns for renters? Government says linked court reforms must precede legislation coming into force, and ministers may lack the headroom for such reforms as an election looms. The opposition says it wouldn’t wait, but will that mean chaos in the courts? Meanwhile, health and safety legislation that followed the Grenfell fire is piling the pressure on social landlords.

The Renters Reform Bill, set to be enacted later this year, puts in place the government’s long-term vision for the private rented sector in England. It is, say housing campaigners, a much-needed piece of legislation. The bill aims to strike a fairer balance between landlords and tenants, addressing poor living conditions and insecurity of tenure.

‘Most landlords provide a good service,’ the government insisted in its response to the Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee’s fifth report of session 2022-23, Reforming the Private Rented Sector. But, it added, ‘the [private rented] sector as a whole currently provides the least affordable, poorest quality and least secure housing of all tenures.’

Under current legislation, a landlord can issue a section 21 notice to take possession of their property without giving a reason with only two months’ notice.

Commitments contained in the new legislation include the abolition of section 21 notices, also known as ‘no-fault’ evictions.

Evictions

In London alone, analysis by the Mayor of London’s office has established that nearly 300 London renters a week face no-fault evictions. Figures published by housing charity Shelter show that the number of section 21 claims started by landlords nationally reached 2,307 last year, the highest in almost five years. Abolishing the process removes the fear of homelessness, the charity argues.

The bill aims to simplify housing tenancies by transitioning them to the status of rolling or periodic tenancies, so that they continue until either a tenant wishes to leave or the landlord is able to prove one of the section 8 grounds contained in the bill. The changes aim to give tenants the flexibility to leave when they want.

‘The problem with section 21 at the moment is that you need to show compliance with a long list of obligations,’ explains George Cohen, an associate at Irwin Mitchell. ‘The bill has abolished section 21 and has expanded the section 8 grounds. It will definitely make things clearer for landlords.’

In its 2022 white paper A fairer rented sector, the government stated that its intention in reforming the section 8 grounds was to ensure that they are ‘comprehensive, fair and efficient, striking a balance between protecting tenants’ security and landlords’ right to manage their property’.

The changes have generally been well received by housing lawyers acting for tenants. Less welcome is the government’s preferred timescale for the abolition of section 21, set out in its response to a report by the Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee.

While the select committee report recommended the creation of a specialist housing court ‘as the surest way of unblocking the housing court process’, the government rejected this. Instead, it said, existing processes needed to be improved.

‘The implementation of the new system will not take place until we judge sufficient progress has been made to improve the courts. That means we will not proceed with the abolition of section 21, until reforms to the justice system are in place,’ the government response noted.

No timeline is available as yet on when these reforms will take place, leading many to allege that ministers have simply kicked the problem into the long grass with a general election looming.

The delays are a blow to those campaigning for an end to no-fault evictions. Labour’s deputy leader Angela Rayner MP accused the government of having ‘betrayed’ renters with a ‘grubby deal’. The Local Government Association called on the government to ‘publish the evidence base establishing, firstly, [that] court backlogs are severe enough to warrant a delay and secondly, that the changes brought in by the bill would have a substantial enough impact on these backlogs to warrant a delay in the abolition of section 21 notices’.

Cohen notes: ‘The government obviously thinks that it can proceed with [the reforms] swiftly, but it is difficult to see how this significant undertaking can be achieved in the foreseeable future. That said, the Renters Reform Bill could be passed before the court reforms are complete, because most of the key changes in the bill will only be enacted by future regulations. The legislation could therefore be finalised and enacted, with sufficient time to implement court reforms before the regime comes into force.’

Other lawyers are frustrated by the lack of information. A possible change of government adds to the uncertainty.

‘The key thing about the general election is that we will probably end up with the key elements of the bill intact under a Labour government,’ says Emma Salvatore, a senior associate at Trowers & Hamlins. ‘But looking at Labour’s proposed amendments, they will probably go ahead with the abolition of section 21 and let the court reforms follow, which will lead to an even bigger mess for landlords.’

Landlord concerns

‘The bill will have a huge impact on landlords,’ notes Cohen. ‘They will need to generate new processes and policies.’

Private landlords will have to join a government-approved ombudsman, regardless of whether they use a letting agent or not. The new scheme will allow tenants to seek redress where their landlord has failed to deal with a legitimate complaint about their tenancy.

The ombudsman will have powers to ‘put things right’. This could include compelling the landlord to issue an apology, take remedial action and/or pay compensation of up to £25,000.

'The bill and the uncertainty over court reforms are putting a lot of landlords off wanting to be in the sector'

Gemma Richards, Moore Barlow

In addition, a new property portal for private landlords and tenants will be introduced. The portal will feature a database of properties and landlords must demonstrate compliance. It will also include information for tenants and councils regarding when, for example, a landlord is subject to a banning order.

Cohen warns: ‘The new property portal could cost landlords with portfolios of property a lot of money.’

Moore Barlow associate Gemma Richards acts for landlords in the private rented sector and notes that a number of her clients are selling up. ‘The bill and the uncertainty over court reforms are putting a lot of landlords off wanting to be in the sector.’

Legal aid lacuna

Figures released by the Ministry of Justice in June 2023 showed that spending on housing legal aid dropped by around £23.5m between 2012-2013 and 2021-2022.

Spending for disrepair cases also slumped.

The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 drastically reduced eligibility for tenants – only those facing a significant threat to health and safety are now able to access legal aid. Damages arising from a disrepair claim were removed from scope.

‘There has been a substantial increase in housing repair cases,’ notes Anthony Gold partner Giles Peaker. ‘The problems arising from insufficient legal aid funding for housing are reaching crisis point – fewer and fewer firms are doing it, and there are a lot of unrepresented people. Unless there is an urgent change in funding, things will only get worse.’

The number of undefended cases is also of concern to landlords, who note that, as a result, cases are taking longer to progress through the courts.

Backlogs and delays

Court delays are a source of ongoing frustration to housing lawyers. ‘The court process is crying out to be reformed,’ says Salvatore. ‘It’s disastrous.’

According to the Ministry of Justice and the National Residential Landlords Association (NRLA), the average time for an eviction to move from notice to possession order is 22 weeks; in extreme cases it can take up to a year.

Eleanor Solomon, partner at Anthony Gold, explains that the court service’s ‘continuing dysfunction’, along with a lack of communication, means that a fast-track disrepair case which once took 9-12 months can now take years.

‘Landlords don’t carry out repairs when they are asked to,’ she says. ‘In the past, after an order for works they would generally be started. Now it is quite common for nothing to happen, and we are having to go back to court to enforce the order. It can lead to a six-month wait while tenants are living in terrible conditions. Social landlords in particular are overwhelmed and are only dealing with things when they have to. From our perspective it means that a case never finishes and it leads to us taking on fewer new cases. Many firms aren’t taking on enforcement work for that reason.’

And it is not just lawyers acting for tenants who feel frustrated. Richards says: ‘I’ve had situations where an eviction notice is still not forthcoming after 14 months. In the meantime, a landlord has a tenant that it doesn’t want. Most of these properties are buy-to-lets and my clients need the money to pay the mortgage on the property.’

‘The promised court reforms would definitely help,’ says Solomon.

The government has identified key areas which need to be addressed before section 21 can be abolished. These include: digitising the court process; considering how courts could prioritise cases which involve anti-social behaviour; improving bailiff recruitment and retention; and providing earlier legal advice to tenants.

Anna Iceton, partner at Moore Barlow, says: ‘The changes to the court process are welcome, but for landlords it prolongs the uncertainty of knowing what to do with their assets while they are waiting for the bill to come into force.’

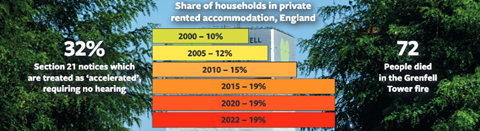

Moreover, the promised reforms could actually place a greater strain on the courts, say housing lawyers. According to the NRLA, figures show that 32% of section 21 notices are treated as ‘accelerated’ claims, meaning there is no need for a hearing and cases can be processed without wasting court resources on unopposed claims.

In its response to last year’s king’s speech, the Law Society warned: ‘The courts are vastly overstretched: possession claims and the eviction process can take many months, sometimes more. The government should outline how it intends to manage increased demand on the courts and what additional resourcing it will put in place to deal with existing backlogs.’

‘When these reforms are implemented, all section 21 notices will need to go through the court,’ explains Richards.

More funding for the court process is unlikely to be forthcoming, says Cohen: ‘We recently issued a possession claim and received a notice saying that the hearing is probably on this day, but it may be moved. My experience is that civil proceedings don’t make headlines, so it would be difficult for the government to justify more funding.’

‘The London courts are incredibly slow,’ Salvatore says. ‘Box work’ is a ‘black hole’ in the court process, she notes, which means that even accelerated section 21 cases, which are undefended, are taking longer.

‘Box work’ is a pile of papers that require judicial attention, Salvatore explains: ‘Even in accelerated cases, the paperwork still needs to be scrutinised by a judge. The whole process can take up to a year. The timeframe from putting a claim in to getting a possession order is around five to six months. It can then take up to six months while we wait for a bailiff to become available.’

Social housing regulation

In the meantime, many buildings, especially social housing, are being found to be unfit. Solomon says: ‘There are two things happening: on all blocks fire safety is an issue, and many 1960s concrete blocks are coming to the end of their useful life. It’s causing a huge amount of disruption.’

The Social Housing (Regulation) Act, which received royal assent in 2023 and is due to be implemented this year, is designed to tackle many of the issues, such as fire safety. The legislation was a response to the Grenfell Tower fire, and the death of Awaab Ishak in Rochdale, who died in 2020 from exposure to serious mould.

The act will allow the regulator of social housing to take action against social landlords and hold them to account with regular inspections. The regulator will also have the authority to issue unlimited fines to landlords.

The increased focus on empowering residents to access redress also grants the Housing Ombudsman additional authority to issue guidance to registered providers following investigations into tenant complaints.

‘Awaab’s law’ provides greater tenant protection against hazards such as damp and mould, requiring registered providers to deal with hazards promptly within certain timeframes.

Housing associations will be required to proactively ensure compliance and staff will be required to engage with residents.

‘The existing law already says that defects need to be remedied within a “reasonable time”,’ notes Solomon. ‘Awaab’s law just tightens this up. It will put timescales on social landlords to remedy defects.’

‘The act is a big stick to ensure that social housing landlords provide fit and proper housing,’ notes Lara Borrett-Lynch, legal director at Foot Anstey. ‘It will lead to far greater scrutiny, which all takes a huge amount of time, effort and money. It also means that social landlords are being distracted from doing what they were set up to do.’

An anxious wait

Landlords, tenants and their lawyers must now await the outcome of a general election which is at most a year away and what it could mean for the progress of reform. For now, they are left hanging, unsure whether it is time to sell up, in the case of landlords, or for tenants whether their rights will eventually be significantly strengthened.

Maria Shahid is a freelance journalist

- A future article will look at Wales’s Renting Homes Act, which the government in Cardiff says is ‘the biggest change to housing law in decades’

2 Readers' comments