The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse made 20 recommendations based on horrific testimony. Yet not one proposal has been implemented, reports Catherine Baksi

The low down

Society has a long history of letting down survivors of child sexual abuse. They suffered harm from their abusers and were failed by the adults and institutions who did not protect them. Those campaigning for changes to prevent the same wrongs being perpetrated on others have also been failed. One opportunity for change was the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, established in 2014. This endured a difficult start and at times lost the confidence of stakeholder groups. The inquiry took evidence from 7,000 victims, and at a total cost of £188m produced a powerful final report in 2022. None of the report’s 20 recommendations has yet been implemented.

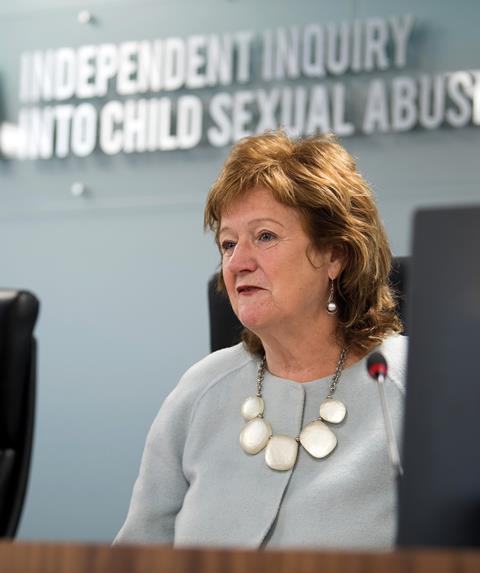

Almost a decade since the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) began and two years after the publication of its final report in October 2022, survivors are still waiting for any meaningful reforms. Chaired by Alexis Jay, a visiting professor at Strathclyde University, the inquiry was set up in 2014 by Theresa May, then Conservative home secretary, in response to a series of child sexual abuse scandals involving celebrities and institutions. Its remit was to ‘consider whether public bodies – and other non-state institutions – have taken seriously their duty of care to protect children from sexual abuse’.

Difficult beginning

Also in circulation, and being treated seriously by the police at the time, were lurid accusations of a Westminster paedophile ring that included parliamentarians. The police response to the latter, ‘Operation Midland’, collapsed when the accusations proved entirely baseless. Accuser Carl Beech was later jailed.

Beset by difficulties at the outset, the inquiry also burned through chairs. The first, Baroness Butler-Sloss, who had chaired the Cleveland child abuse inquiry in 1987, stood down after objections were raised that her late brother, Sir Michael Havers, was attorney general in the 1980s, a period the inquiry would review.

Dame Fiona Woolf, a former Law Society president and lord mayor of London, stepped down amid calls for her to resign over her links to the Westminster political establishment. New Zealand High Court judge Dame Lowell Goddard also quit, in August 2016, saying the inquiry was beset by a ‘legacy of failure’.

The same year, the inquiry also lost its lead counsel Ben Emmerson and second lawyer Elizabeth Prochaska. It also lost the support of victims’ groups, including the Shirley Oaks Survivors Association, which represented hundreds of victims of abuse in Lambeth children’s homes, and the Survivors of Organised and Institutional Abuse.

Operation Midland proved a wild goose chase. Yet collecting credible testimony of widespread child abuse, and attendant official indifference, remained a mammoth task.

The inquiry held scores of public hearings, work that ended in 2020 after taking evidence from 7,000 victims and conducting 15 investigations. The latter triggered numerous reports on religious institutions, councils, schools and individuals, as well as focusing on abuse by organised crime, the impact of the internet and the issues of reparations.

The inquiry’s final report ended with the damning conclusion that ‘horrifying and deeply disturbing child abuse’ was ‘endemic’ – and an ever-growing problem exacerbated by the internet.

The report detailed failings across civic society. From the government to the police, to religious bodies, it found institutions ‘prioritised their own reputations, and those of individuals within them, above the protection of children’.

Key proposed reforms included the creation of a national compensation scheme, the introduction of a criminal offence for people who work with children failing to report allegations of child sexual abuse, and the creation of child protection authorities in England and Wales.

None of these recommendations has been acted on.

Kim Harrison, president of the Association of Personal Injury Lawyers (APIL), is damning: ‘It is shameful that there seems to be little sense of urgency to get on and put things right.’

‘Accountability remains as elusive for survivors today as it did when IICSA came into existence,’ says Alan Collins, a partner at Hugh James.

Not all the proposals are unproblematic, however. Some do not go far enough, say lawyers. Alison Millar, a partner at Leigh Day, criticises the previous government’s proposed mandatory reporting for being limited to cases in which a person has actual knowledge that a child is being sexually abused. This, she says, ‘deprives the recommendation of much of its teeth’.

There would be no sanctions on people or organisations made aware of concerns raised by third parties who then fail to pass the information to social services or police.

Following the inquiry’s recommendations, in February this year, then home secretary James Cleverly and Laura Farris, minister for victims and safeguarding, announced plans to make it a legal requirement for anyone undertaking regulated activities involving children in England and Wales, including teachers or healthcare professionals, to report if they know a child is being sexually abused.

Under this proposed requirement, anyone who fails to report child sexual abuse which they are aware of could be barred from working with young people. Anyone who tried to protect abusers, by intentionally blocking others from reporting or covering up the crime, would be guilty of a criminal offence, punishable by up to seven years in prison.

‘There is no excuse for turning a blind eye to a child’s pain,’ said Cleverly. He added that the government was ‘working at pace to get a mandatory reporting duty for child sexual abuse onto the statute book’.

Jay says she was ‘deeply disappointed’ by the measures that emerged and which were set out in an amendment to the Criminal Justice Bill. Abuse survivors have branded them ‘worse than useless’. While there has been a call for evidence and a consultation, no law has been enacted. In any case, the Criminal Justice Bill fell in the parliamentary ‘wash-up’ after the general election was called.

The only other recommendation to which the Conservative government was committed was a redress scheme, as an alternative to civil actions. In May 2023, the government said it would consult on establishing a compensation scheme. Home secretary Suella Braverman said: ‘No apology or compensation can turn the clock back on the harrowing abuse these victims suffered, but it is important survivors have that suffering recognised and acknowledged. That is what the scheme will deliver.’

The IICSA had recommended that the government set up a scheme funded by central and local government and ‘voluntary contributions sought from non-state institutions’, similar to models introduced in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Jersey. But lawyers considered this unsatisfactory.

Collins, who played a part in the establishment of two such schemes in Jersey, says ‘they have much to commend them’ as a way of ‘delivering some justice, albeit belatedly’. He adds that the money should come from those responsible for causing the harm rather than taxpayers, adding that a scheme should also pay ‘meaningful’ amounts of compensation.

The criminal law, in the form of the Powers of Criminal Courts (Sentencing) Act 2000 provides for offenders to pay compensation to victims. But Collins says it is rarely used in sexual abuse cases.

Ministry of Justice data shows that only around 0.02% of criminal compensation orders relate to child sexual abuse cases. Collins says it is ‘unforgivable’ that the justice system does not use its existing powers to make offenders accountable for the harm they have done.

‘It would be wrong for the taxpayer to pick up the full cost of the scheme when many of the institutional defendants, such as religious organisations, are wealthy and powerful, with insurance to cover claims,’ says Harrison.

If a compensation scheme were to be funded by the public purse there would be immense pressure to keep payments low, Harrison adds.

Harrison wants the Labour government to ‘pick this up without further delay’ so that those who cannot face pursuing civil claims get redress.

Any redress scheme, Millar stresses, must be accessible to the many survivors who have additional needs and provide external support to complete paperwork; cover all types of abuse, including emotional abuse and neglect; and provide support to victims in obtaining the necessary background information.

A scheme should not require survivors to sign a ‘waiver’ or compromise their rights to receive legal advice, she adds, adding that there is also merit in providing ‘common experience’ payments and offering non-financial redress, such as apologies and signposting to counselling.

IICSA’s 20 recommendations

After releasing its report in October 2022, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse made 20 recommendations.

- Compile and publish a single core dataset covering both England and Wales on a regular basis, including the characteristics of victims and alleged perpetrators of child sexual abuse, vulnerability factors, and the settings and contexts in which abuse occurs.

- Create Child Protection Authorities for England and Wales to improve child protection practices.

- Create a Minister for Children for England and Wales.

- Commission regular campaigns to increase public awareness of child sexual abuse.

- Ban the use of techniques that deliberately induce pain in youth justice settings.

- Give children in care the ability to challenge aspects of local authority decision-making by amending the Children Act 1989.

- Create a registration system for care staff in children’s homes.

- Introduce a registration system for care staff in young offender institutions and secure training centres.

- Extend the use of the barred list to anyone recruiting an individual to work or volunteer with children on a frequent basis.

- Improve compliance with the statutory duty to notify the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) through inspections, arrangements to refer breaches to the police and an information-sharing protocol between the DBS and regulators.

- Introduce legislation to allow enhanced checks of citizens and residents of England and Wales who apply to work or volunteer outside the UK.

- Make it mandatory for internet companies to pre-screen material for known child sexual abuse images before it is uploaded.

- Introduce laws requiring anyone working in regulated activity, a position of trust, or as a police officer, to report child sexual abuse if they receive a disclosure, witness, or observe recognised indicators of child sexual abuse.

- Commission an inspection of compliance with the Victims’ Code (tinyurl.com/58cw6hav) in cases of child sexual abuse.

- Remove the time limit for compensation claims.

- Provide specialist therapeutic support for all children who have experienced sexual abuse across England and Wales.

- Introduce a code of practice for keeping and accessing records about child sexual abuse.

- Extend the Criminal Injuries Compensation Scheme.

- Set up a single redress scheme to provide monetary compensation for people who were sexually abused in institutions in England and Wales.

- Ensure internet companies introduce age verification systems.

Limitation period

The last government rejected a key inquiry demand, which was to abolish the period during which a victim of sexual abuse can pursue a civil claim for injury.

Under the current law, child sexual abuse cases in civil courts are subject to the same three-year limitation period as personal injury claims, subject to a court’s discretion under section 33 of the Limitation Act to grant extensions if there are legitimate reasons for a delay. That time runs from the date of the alleged abuse or knowledge of abuse, or when the victim turned 18.

The inquiry heard that nearly all claims relating to historical child sexual abuse are brought outside the standard time limit, as it can take ‘decades for survivors to feel able to discuss their sexual abuse’.

Research by the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Adult Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse found it takes an average of 26 years for victims to disclose abuse. For a case to proceed after the limitation period, the victim must prove that a fair trial can proceed despite the length of time between the abuse and reporting it.

Instead of removing the limitation period, the last government proposed reversing the burden of proof, so that the defendant would be required to show a fair trial could not take place due to the passage of time.

'Child sexual abuse is utterly abhorrent and we must protect the interests of these victims and survivors'

Lord Bellamy, justice minister 2022-2024

In a consultation that closed in July, a few days after the general election, the outgoing government had included the option of removing the limitation period but made it clear it did not support it. Its favoured proposal was to strike a balance between the rights of victims and survivors to seek justice and compensation, and the need to ensure a fair trial for defendants.

In May, Lord Bellamy, who was a justice minister from June 2022 until July 2024, said: ‘Child sexual abuse is utterly abhorrent… However, we also know limitation periods play an important role in ensuring defendants’ rights to a fair trial, which is why our proposal to reverse the burden of proof strikes the right balance.’

Michael Edwards, a barrister at 4PB, disagrees, describing the current limitation period as an ‘obvious injustice’. Harrison points out that abolishing the limitation period in cases of ‘non-recent’ sexual abuse would bring the law in England and Wales into line with Scotland.

In its response to the consultation, APIL urged the Labour government to bring forward the IICSA’s recommendation to abolish the time limit on child sexual abuse claims ‘without further delay’.

‘It is vital that any changes to the limitation legislation result in a removal of the time limit for child sexual abuse claims,’ said APIL. ‘If new legislation is introduced which still retains the three-year time limit, this will inadvertently make the limitation barrier even more difficult to overcome.’

Collins also argues that the IICSA’s proposal to scrap the limitation period while stressing the ‘express protection of a fair trial’ merely retains ‘limitation by the back door’.

‘If the defendant can show that it cannot properly assess the claim it faces, let alone defend because, for example, the alleged abuser is dead, it will cry, whether justly or not, that [the claim] is prejudiced,’ he says.

In other jurisdictions that have adopted similar frameworks, claimants have been denied the opportunity of a trial after courts ruled that the burden on the defendant would be too great.

A ‘more humane’ system

In 2016, Victoria McCloud, a now-retired High Court judge who dealt with many non-recent sexual abuse civil claims, formed the Historic Abuse Lawyers Forum. This consultative group, composed of solicitors, barristers and other court users, sought to improve how such claims are managed when the defendant is an institution and the claimant is accepted to be a victim of abuse.

‘I was inundated with positive suggestions from all sides, including defendant lawyers and insurers,’ says McCloud.

One suggestion that the group considered was McCloud’s idea to ‘implement a more humane system where help and support [is] provided by insurers from the start, making recovery and the court process synergistic instead of antagonistic, and where the court case is about producing [a] narrative decision collaborated in by all sides to ascertain what happened and how it can be prevented in future’.

The aim, McCloud adds, was to develop a process akin to air crash investigations which would ‘seek justice for both sides and for potential future victims, respecting the evidence which victims can give and what we can learn from it’.

But McCloud says that despite being cited positively in inquiry reports, her psychological, victim-centred approach was ‘closed down by one very abrupt unexpected phone call to me from a very senior judge, with no reason given’.

Adding her voice to that of other lawyers, McCloud urges the Labour administration to pick up the baton of reform.

A government spokeswoman told the Gazette: ‘The minister for safeguarding, Jess Phillips, has met with victims, survivors and child protection experts and will continue to listen and engage. We are considering where further progress can be made against the recommendations of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.’

The Conservative government’s consultation on reforming the limitation period closed on 10 July. The Labour government is considering its submissions and plans to issue a response shortly.

Loophole

If the new government does choose to act in this area, human rights lawyers at Leigh Day say it should make an important additional change in the law. The firm is currently working to close a loophole created by section 6 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956, which governed sexual abuse cases between 1956 and 2004.

The loophole meant that girls who made allegations of unlawful sexual intercourse between those years and were aged between 13 and 16 at the time had a maximum of 12 months to report the offence to the police, after which their allegations were time-barred.

On behalf of a client, referred to as ‘Lucy’, Leigh Day made an application in August to the European Court of Human Rights, arguing that this 12-month procedural bar breaches applicants’ human rights.

In the late 1980s, when she was 13 to 15 years old, Lucy was groomed and abused by a man 22 years her senior, who later admitted the offence to police.

Lucy’s lawyer, Tessa Gregory, a partner at Leigh Day, says the loophole affects many other victims and means ‘perpetrators of serious sexual offences are likely to walk free’.

That is exactly the sort of outcome which undermines public trust in the ability of the law to hold child sexual abuse offenders to account – a loss of faith akin to that which led to the creation of the IICSA in the first place.

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist