THE LOW DOWN

It is time for the Court of Protection (CoP) to come of age, its vice-president Mr Justice Hayden tells the Gazette. He is determined the court should shake off its ‘secretive’ image. He has plans to require judges and advocates to wear robes when sitting in CoP hearings in the High Court to make it clear it is open to the public and media, and that it wants to engage in informed public debate. Hayden also wants to ensure the CoP does not drop behind in the digital reform programme and to set up a formal rules committee. CoP work is a significant practice area but it demands an innovative approach, with hourly guideline rates stuck at 2010 levels and legal aid limited in scope. Practitioners also warn of delays in the court process and raise concerns about increasing reports of abuse of elderly and vulnerable clients.

The Court of Protection (CoP) is determined to shake off the outdated image that it is the ‘most secretive court in Britain’ and engage in public debate on the most fundamental and emotionally charged issues of life and death and individual capacity.

Mr Justice Hayden, in his first interview since taking over as vice-president in the summer, says these issues ‘cannot be and ought never to be’ heard behind closed doors. He is planning a series of measures to enhance the court’s role, including requiring judges and advocates to wear robes during CoP hearings in the High Court to send a clear signal that its doors are open to the public and media.

He will also set up a formal rules committee to replace the ad hoc committee and a judicial engagement group so the court does not ‘drop through the net’ in the digital reform programme. ‘It is time for the [CoP] to come properly of age and be a senior court of record,’ he tells the Gazette.

The CoP was created by section 45 of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 with the jurisdiction to deal with decisions for anyone over 18 who is assessed as lacking decision-making capacity.

The MCA has, at its core, the fundamental principle that a person must be assumed to have decision-making capacity unless it is established that he or she lacks it. But, after just over a decade, has it achieved its ambition to deliver an ‘empowering’ ethos?

The CoP’s duty is to decide what is in the ‘best interests’ of the cared-for person. Most applications coming before it involve non-contentious property and financial decisions. But it is decisions concerning health and personal welfare – medical treatment decisions, whether someone has the capacity to consent to sex or marry, where they should live – that can lead to the most sensitive cases.

Decisions concerning capacity have to be negotiated with enormous skill, says Hayden, stressing the importance of the court respecting an individual’s autonomy to take bad as well as good decisions.

‘Then there are the challenging categories of case where the bad decisions are so dangerous to them that, even if they are capacitous, we might have to invoke the very rarely used parens patriae, the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court in relation to vulnerable adults.’

But, he warns, ‘if you start taking decisions for a potentially capacitous adult you identify as vulnerable against their express views, you are in very, very challenging territory’.

Three recent cases show the range of issues facing judges. Earlier this month, Hayden allowed a man suffering from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease to die after approving a plan for doctors to stop providing life-support treatment. Last month, he found that a court-approved care plan which resulted in a young woman with autism being sexually exploited by a number of men had compromised her ‘safety and dignity’.

In both cases, he stressed the importance of informed public debate: ‘When you do that you often get a healthy synergy which helps people to get to better solutions.’

He adds: ‘I am absolutely clear if you are discussing something so fundamental as life and death, or some medical intervention that will either protect life or terminate it, that cannot be and ought never to be behind closed doors.’

Last week, Hayden set a timetable for a test case over welfare deputyships being brought by three parents of young adults with learning disabilities. The three, including Rosa Monckton, wife of journalist Dominic Lawson, are seeking a change in the law to make it easier for parents to be granted a welfare deputyship to deal with their children’s affairs once they reach 18.

Alex Rook, public law partner at Irwin Mitchell, specialises in welfare issues. He is acting for the three parents, who raised nearly £30,000 on the crowdjustice website to fund the case. He has filed videos with the court showing Domenica Monckton and another young adult chatting about who they would like to support them.

He says parents feel marginalised by the state when their children turn 18 because the MCA’s code of practice says that welfare deputies should be appointed only in the most difficult cases. ‘We recognise the court might prefer to make one-off decisions in a particular dispute,’ he says. ‘What we are talking about are constant ongoing decisions. We believe it is within the court’s remit to decide the code is wrong and give clarity on this issue.’

Overall, he believes the MCA is a ‘good piece’ of legislation and the court processes work. ‘But, on the ground, the ideas behind the act are still not embedded in the decision-making of health trusts and local authorities, so I am regularly asked questions which shouldn’t require a lawyer.’

Earlier this year, the Supreme Court decided in N v ACCG [2017] UKSC 22 that the CoP’s jurisdiction should not be used to apply undue pressure on public bodies to make more resources available than would otherwise be the case for a person’s care. Judicial review was the proper process to scrutinise resource-allocation decisions.

‘ZERO INTOLERANCE’ FOR LAWBREAKERS

Practitioners and the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) are concerned about increasing reports of abuse of elderly and vulnerable people by their attorneys or deputies. The OPG carried out 1,897 investigations in 2017/18 – a 50% increase on the previous year – with most involving attorneys. These led to 459 applications to the court to discharge the attorneys or deputies compared with 272 in 2016/17.

The increase has to be seen in the context of the huge growth in lasting powers of attorney (LPAs), which passed 3 million last year, and the increasing number of deputyships – 60,000 – being supervised by the OPG.

The OPG has made it clear that it will take a ‘zero tolerance’ approach to any attorney or deputy who breaks the law and it will refer cases to the police or CPS. Over the last year, it has lowered the threshold for triggering an investigation and will increase its investigative team by nearly a fifth by the end of 2018/19.

Examples of abuse in previous years have included undervalued house sales, the client’s home being sold to the attorney, large financial sums transferred from the client’s bank account to another bank account and creating fraudulent LPAs.

The OPG wants the LPA application process to be fully digital. Jan Sensier, OPG’s deputy director of strategy, has said that replacing wet signatures with e-signatures would free up resources which would be redirected towards preventative safeguards. There are fears, however, that fully digital LPAs could be abused.

However Sir James Munby, the former president of the Family Division, recently raised concerns that desperate parents were using the family and CoP courts to force health trusts and public authorities to act. He also warned that the courts were being denied the tools to further the welfare of cared-for individuals.

Hayden supports his concerns. While mental health services were allocated ‘quite significant funds’ in the recent budget, he says, ‘there is no doubt that the funding of mental health services for children and adults has fallen well below what I think most people think it reasonable to expect’.

This is ‘incredibly frustrating’, he says. ‘However, in a recent judgment, I made the point that the court shouldn’t be used as a headmaster to get people to do what they ought to be striving to do in any event.’

He is also concerned about delays in some cases. He says the rules relating to experts are being ‘too generously interpreted’ by judges and practitioners in the hope they will come up with something ‘illuminating’.

‘One of the concerning features of the MCA is that it doesn’t embody the imperative of avoiding delay,’ he says. While he is not suggesting decisions should be taken ‘precipitously’, he warns ‘delay is often inimical to P’s [protected person] interests’.

What is clear is that CoP work has developed into a significant practice area, with its own league tables. Practitioners generally specialise in either property and financial decisions, or health and welfare issues. But both require them to be innovative, as guideline hourly rates for property and financial matters have not risen for eight years and legal aid for welfare issues is limited in scope.

Fiona Heald, chair of the Law Society’s Private Client Section committee, is head of the CoP team at Moore Blatch. ‘The biggest problem for me is that the court is struggling with the amount of work, with an ageing population and more and more people suffering from mental incapacity,’ she says.

‘I have sympathy with the pressure the CoP is under. But we are currently being told six to eight weeks for someone to look at an issue and, sadly, our clients have a tendency to blame us for any delays.’

Eddie Fardell, head of the CoP team at Kent practice Thomson Snell & Passmore, finds the court ‘slow in processing applications. The helpline is ineffective – if answered at all; the fast-track application process isn’t fast enough; application papers go missing or aren’t read properly; while a team member was left on hold for 90 minutes.’

Yet, he points out, the court fee was reduced recently by the Ministry of Justice, ‘which seems nonsensical when it can’t provide the service needed’.

Holly Chantler, head of private client at Morrisons Solicitors and a director of national organisation Solicitors for the Elderly, says members are concerned about: delays in making deputyship orders in uncontested applications; an increase in cases where the court fails to comply with its own directions; and delays in making and issuing orders.

On a positive note, she says problems over cases being listed or applications being issued have diminished as shortages in administrative staff and judges have been resolved ‘to some extent’.

Judge Carolyn Hilder (pictured at the top of this article and right) took over as the CoP’s senior judge in 2016. Based in the Central Registry in First Avenue House, High Holborn, she is regional lead judge for London and national lead judge responsible for co-ordination and communication throughout all the regions.

There are seven regional hubs, each with a lead judge, which feed out to local courts. Some applications are issued locally but all property and affairs matters are issued through the Central Registry, which has just five court officers.

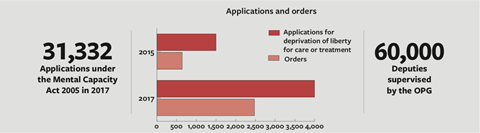

Hilder says the CoP’s casework topped 30,000 applications for the first time last year and the trajectory remains upward. The target is to get non-contentious property and affairs cases to final order within 16 weeks.

She acknowledges that the court is not meeting that target in all cases after some significant staff changes. However, she says there are remedial initiatives under way and the MoJ is looking at the resourcing model.

There are just over 300 nominated CoP judges who all volunteer for the role. ‘No one is forced to sit, Hilder says. ‘The nature of the work can be very emotionally draining and it is a responsibility I don’t think any judge wears lightly.’

A new system was put in place this year whereby Hilder and the regional leaders identified where they needed nominated judges. London and the south-west identified a need for a pool of deputies. The 85 nominated judges include, for the first time, 12 deputy district judges and 18 tribunal judges.

‘The role inspires a high degree of enthusiasm,’ Hilder says. ‘There aren’t many of us who can’t point to something in our lives which brings us into contact with the court. So many of us have parents battling with dementia or children with learning disabilities. ‘If you go home at the end of the day without being a little bit emotionally exhausted, you haven’t, as one judge put it, put your heart and soul into it.’

On casework, the CoP is seeing a significant increase in applications for deprivation of liberty for the purpose of care or treatment. These have more than doubled, from nearly 1,500 in 2015 to nearly 4,000 last year, with the number of orders rising from 644 to 2,477.

Hayden says recognition of the importance of considering deprivation of liberty has become so tightly drawn that it requires judges to consider it in vastly more cases than they used to. ‘The whole issue has to be kept under very close review and I think the law has, as yet, some way to evolve,’ he says.

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards were introduced in 2009. Concerns over their effectiveness prompted the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Bill to replace them with Liberty Protection Safeguards.

There aren’t many of us who can’t point to something in our lives which brings us into contact with the court. So many of us have parents battling with dementia or children with learning disabilities

Judge Carolyn Hilder

The Law Society issued a highly critical response to the new protections, arguing that the scheme was not sufficiently robust or comprehensible.

The Department of Health has subsequently issued amendments, including extending the safeguards to 16/17-year-olds and explicitly stating that the cared-for persons’ wishes must be considered. But Sheree Green, chair of the Law Society’s Mental Health Committee, says the amendments do not go far enough and the Society will continue to campaign for changes as the bill goes through its final stages.

As the CoP’s casework continues to grow, Hayden says: ‘Above all else, what has to be appreciated is that the CoP’s philosophy is investigative, non-adversarial sui generis rather than adversarial. That has really got to settle in.’

And that fits in with his determination to engage the public in the CoP’s decision-making, while protecting the privacy of those at the heart of the cases by a transparency order. Live tweeting is allowed as long as reporting restrictions are respected.

However, Hayden stresses the court also has to be ‘vigilant’ that judges aren’t put under too much pressure by what is said on social media and that threats are not trivialised.

What is beyond doubt is that the court is going to become increasingly important with an ageing population and the challenges presented by advances in medicine.

‘These issues are going to come more and more into the public eye which is why I think the public need to know what we are doing and why we are coming to the decisions we are,’ Hayden concludes.

Grania Langdon-Down is a freelance journalist

No comments yet