The low down

In the police investigation of the murder of black London teenager Stephen Lawrence by a gang of white youths, the force’s ineptitude fused with racist assumptions. Both flaws lengthened the path to justice for Lawrence and his family by many years. The inquiry into his murder, by retired judge Sir William Macpherson, identified and defined ‘institutional racism’ for the modern age. Macpherson paved the way for the public sector race equality duty, in force from 2001. The two decade mark is an opportunity, in Black History Month, to reflect on its achievements, flaws and legacy.

A visitor to south London curious to see where The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, headed by retired judge Sir William Macpherson of Cluny, was conducted will be disappointed. Hannibal House, along with the Elephant and Castle shopping centre that it sat above, was demolished in April. There is now no trace of the room where shocking testimony exposed the racism and incompetence that marred the investigation into Lawrence’s 1993 murder.

Instead, Macpherson’s report, presented to parliament in 1999, has its monuments in law. The Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000 required public authorities to promote racial equality through a ‘general duty’. On 23 October 2001 home secretary David Blunkett used his powers under the act to specify processes for public bodies that would constitute compliance, through SI 2001 No. 3458.

Henceforth, public bodies caught by the change – including not just the police, but councils, government departments and even the BBC – had to ‘have due regard, when exercising their functions, to the need to eliminate unlawful racial discrimination and to promote equality of opportunity and good relations between persons of different racial groups. The duties are imposed for the purpose of ensuring the better performance of the general duty’.

Any long-established white-dominated organisation is liable to have procedures, practices and a culture which tend to exclude or disadvantage non-white people

Jack Straw speaking in the Commons, 1999

The goal was clear. Public bodies should positively promote race equality, and avoid actions that had a discriminatory outcome. And they must plan accordingly. This equality duty was later replicated for disability (2006) and gender (2007), before all three were subsumed into the Equality Act 2010. But in 2000 the duty broke new ground, and the UK remains unique among mature democracies in having such a duty in law.

The Home Office drafted the race equality duty in close consultation with the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE). Barbara Cohen, the senior lawyer at the CRE with responsibility for shaping the duty, recalls a ‘really positive time… heady’.

The principle of placing this form of duty on public bodies had just two precedents in UK law, Cohen tells the Gazette. The first was the Northern Ireland Act 1998, where it existed to balance the rights and interests of unionist and nationalist communities. The second was the Greater London Authority Act 1999, which established London’s elected mayor and assembly.

After Macpherson, it was clear the government would bring in such a duty. But how far would it go? Cohen cites the first obstacle the CRE faced in promoting far-reaching reform – the Home Office’s first draft of the bill did not include indirect discrimination.

The late human rights barrister and Liberal Democrat peer Lord Lester, who had a key role in the Race Relations Act 1976, shared Home Office scepticism on this point. But to Cohen and her colleagues at the CRE, the problem was obvious. ‘Criteria could look neutral,’ she points out, yet have an ‘impact’ that was discriminatory.

Eventually, the Home Office was won over and redrafted to encompass indirect discrimination. That point established, attention turned to the enforcement of the duty. The scale of its application was a success for race equality campaigners; yet with a scope which in education alone included 25,000 schools, it was daunting.

The CRE, Cohen notes, could not be expected to take on the task because it did not have the resources. So she approached the National Audit Office and others, seeking clarity. Reassurances were given that enforcement would, by implication, be a matter for the regulatory bodies that oversaw every public body. ‘Sadly, that’s never really operated,’ Cohen reflects. Public bodies ‘self-identified how they met the duty’ and regulatory bodies had neither training nor a monitoring mechanism in place.

Race for inclusion

Through 2020 the Law Society worked with its Ethnic Minority Lawyers Division to understand the experience of black and ethnic minority solicitors at different points in their careers. The research acknowledged a record of action within firms. But despite this, the Race for Inclusion report concluded ‘little appears to be changing in terms of black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors’ experiences’.

The proportion of black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors within the Solicitors Regulation Authority population is increasing at a very similar rate to black, Asian and minority ethnic representation in the UK working age population. But that seeming balance masks significant anomalies.

Black solicitors, the report noted, make up 3% of the profession, whereas Asian solicitors comprise 10%, which is nearly double the proportion in the working age population.

Organisational culture was criticised. Participants frequently reported feeling like an outsider and not being given the same opportunities as white colleagues – in City firms especially. Almost all participants had experienced some level of microaggression based on their ethnicity.

Retention rates for black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors, the research showed, are lower in larger City firms than for their white peers.

For more information, click here.

View from Whitehall

How was this radical new duty viewed in government and the civil service? As home secretary there had been no doubting Blunkett’s predecessor Jack Straw’s determination to take up Lawrence’s case. Straw met Lawrence’s parents in early 1997 and again within weeks of Labour’s general election victory that year. In July he announced a full judicial inquiry.

Straw also kick-started the review of the ‘double jeopardy’ law that eventually enabled the conviction of Lawrence’s murderers in 2012. This followed the failure of a private prosecution brought by Lawrence’s parents.

The Macpherson report covered both the police investigation into Lawrence’s murder and wider lessons to be learned.

On Macpherson’s landmark finding of ‘institutional racism’ in the police, Straw told the Commons that he and the Met commissioner accepted the report’s definition of ‘the collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin’.

He added: ‘In my view any long-established white-dominated organisation is liable to have procedures, practices and a culture which tend to exclude or disadvantage non-white people. And the police service is little different from other parts of the criminal justice system or from government departments, including the Home Office, and many other institutions as well.’

In practice, however, the machinery of government would exhibit deep uncertainty over how best to respond to the duty. Cohen had encountered the Home Office’s initial resistance to including indirect discrimination. Now, with the scope of the duty cast, it was time for the Cabinet Office, charged by the prime minister with overseeing the running of government departments, to plan its superintendence. Government departments would now be caught by the race equality duty – and the need to observe it had to be built into decision-making.

From 1999 until 2003 Sandra Kerr was a civil servant working in the Cabinet Office on equality and diversity issues. ‘I remember the thinking around [the duty] was that it might be more relevant for some government departments than others,’ Kerr says.

What emerged was a consensus that departments that engaged continually with the public, such as the Home Office, and those which became the Department for Work and Pensions (and also the Crown Prosecution Service) would be greatly affected. The response was ‘two levels of guidance’, she recalls, and the framework for action adopted for each level was ‘manifestly different. With hindsight, I don’t believe the civil service across the board gripped this’.

In sex discrimination cases, [you find] people still say openly discriminatory things. With race, it’s often more subtle

Shantha David, Unison

In the courts

The race equality duty had its roots in a desire to correct racist culture and practices in public bodies before their presence could adversely affect the ability of those bodies to do a good and fair job. The clear intention was preventative.

But the duty might also provide new grounds for seeking a remedy through the courts where a public body was alleged to have failed in discharging the duty. From its early days the duty was litigated, in turn providing and developing the jurisprudence.

Bindmans partner John Halford is now joint head of the firm’s public law and human rights team, but had been at the firm for just a year when a call from a ‘Mrs Elias’ led to his first race equality duty case.

At issue was a compensation scheme devised by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) for British citizens detained by Japan after the fall of Hong Kong in 1941. In 1999 and 2000, while the Home Office was grappling with the design of the race equality duty, the MoD was deciding on criteria for compensation to be paid to former internees.

But who was British? Within ‘the empire’ the designation ‘British subject’ had once applied very widely. How to limit the scheme without excluding children of Britons born abroad? In 2001, the MoD’s answer, Halford explains, amounted to ‘a blood link to the UK’. A challenge brought by the Association of British Civilian Internees (ABCI) reached the Court of Appeal in 2003, where it failed.

Among ABCI members was Diana Elias. Born in Hong Kong in 1924, she and her parents were British subjects, but she did not meet the ‘blood link’ criterion. ‘She had written numerous letters to the MoD saying “this is a racist scheme”,’ Halford recalls. With the failure of the ABCI case, Elias began calling solicitors who might represent her. Until she called Halford, each had turned her down because of the ABCI judgment. But the scheme’s discrimination seemed clear to Halford, and the court had not considered whether the scheme was in breach of the still-youthful race equality duty.

In 2006, the Court of Appeal agreed and found for Elias. Significantly, Halford points out, Elias proved the duty was enforceable.

Other instructions followed for Halford, resulting in defining judgments that have clarified equality duties.

In 2007, the High Court held that an English language-based test devised by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence was discriminatory. The test was used to determine access to medicine that slowed the effects of Alzheimer’s disease in its early stages. (The negative impact of the test also applied to people with learning disabilities.)

A 2010 Court of Appeal case determined that Haringey Council had acted unlawfully when failing to consider the race equality impact of a multi-million-pound development.

In 2015, the Court of Appeal decided that Swansea Council’s decision to cut school transport for faith schools, but not Welsh language schools, was unlawful. As Halford recalls, when the race demographic of the faith schools affected was compared with that of the language schools the failure under the race equality duty looked clear. Some 30%-40% of most faith school pupils affected were non-white, whereas the figure for Welsh language schools was negligible.

With the relevance of equality duties established, Halford says cases have entered a ‘second wave… where things have got stickier’. Public bodies, he says, generally accept the scope of their equality duties. At issue today is what constitutes ‘due regard’ and what is ‘proportionate’.

So far, he says, the courts have pointed out that equality considerations ‘can’t be perfunctory’ or merely a ‘tick-box’ exercise. Further clarity on these points is lacking.

And what of the race equality duty’s wider effect?

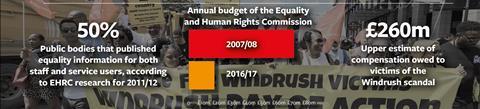

The CRE has been replaced by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), just as the Equality Act 2010 subsumed separate legislation on race, gender and disability. The Equality Act was one of the last pieces of legislation passed by the outgoing Labour government. New prime minister David Cameron, pursuing a ‘war on red tape’, singled out the task of carrying out equality impact assessments for special criticism.

‘I care about making sure we treat people equally,’ Cameron told the CBI’s annual conference in 2012. ‘But let’s have the courage to say it – caring about these things does not have to mean churning out reams of bureaucratic nonsense… We don’t need all this extra tick-box stuff. So I can tell you today, we are calling time on equality impact assessments.’

As with the prime minister’s promise to limit judicial review, made in the same speech, the speech proved to be more about messaging than action. Kerr is critical of the consistency in quality of equality duty assessments, but says she continues to see very good examples, including from HMRC.

Perhaps there remains a bigger problem for all equality duties. Shantha David, head of legal services at Unison, says the lack of ‘ownership’ that has existed since the inception of the duty continues to hamper attempts to enforce it. ‘The EHRC has been slow on picking organisations up,’ is her assessment.

In an employment context, she points out, details of a case may be sealed by a settlement agreement, meaning that further investigation of what may be a more extensive problem in a public body is not uncovered. A reliance on litigation to enforce is also problematic, she says: ‘In sex discrimination cases, [you find] people still say openly discriminatory things. With race, it’s often more subtle.’

David adds that the significance of the duty is such that when an unlawful policy is brought to the attention of organisations, ‘they do change policies’. But too often, a proactive approach is lacking.

Discrimination lawyer Audrey Ludwig, who leads the Suffolk Law Centre, agrees that the impact of the duty can be softened through lack of commitment. ‘The initial optimism foundered with the lip service often paid to it by public bodies and the practical difficulties of funding public law claims for breaches,’ she tells the Gazette.

And, as Kerr argues: ‘If the Home Office had done a proper impact assessment, the “Windrush scandal” would never have happened.’ Instead, as a result of its ‘hostile environment’ immigration policy, the department faces an estimated compensation scheme bill of anywhere from £60m to £260m over Windrush, and a huge loss of confidence in its commitment to race equality.

Perhaps it is too soon to hand down a verdict on the significance and legacy of the 2000 act and SI 2001 No. 3458. To some degree it remains a work in progress.

Ludwig says: ‘While not blind to its limitations, the race equality duty was an important step in requiring better-evidenced public policymaking.’

‘The duty,’ Halford notes, ‘is still really important. It would be disastrous if it was removed. But it would be good if steps formalised how to discharge it. I can advise on how to do it legally. But it shouldn’t need legal advisers – a senior [non-lawyer] should be able to discharge it.’

Hannibal House, where Macpherson heard evidence that led him to construct a modern, accepted definition of institutional racism, may have turned to dust. But the principle of an equality duty endures. With hindsight, it could be that the legacy of the duty we look for is not a building, but a foundation.