What does the evolution of international criminal law enforcement portend for the prosecution of alleged war crimes committed in Ukraine? Catherine Baksi reports

The low down

International criminal law enforcement operates where justice, superpower politics, human rights and war intersect. This greatly complicates the prosecution of alleged war crimes – as does the fact that this is a relatively ‘young’ discipline originating in the tribunals that sat after the second world war. Ad hoc tribunals and the International Criminal Court have achieved a great deal in the last 30 years, but arguably not enough. The ‘great powers’ protect both themselves and their allies. So what does this portend for Ukraine, where evidence of war crimes committed following Russia’s invasion – a year ago today – continues to be uncovered?

Russia invaded Ukraine a year ago today. Its authorities and armed forces have since been accused of committing numerous war crimes, including the massacre, rape and torture of civilians. There have also been reports of forced deportation, hostage taking, arbitrary detentions, disappearances, and mistreatment of prisoners of war (by both sides, in the latter case).

In March, less than two weeks after the invasion, Karim Khan KC, the British barrister who is chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), opened an investigation into all ‘past and present allegations of war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide’ committed in Ukraine since November 2013. In a statement, he said that his office at the ICC had ‘a reasonable basis to believe crimes … had been committed’.

The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, which was set up by the United Nations Human Rights Council the same month, and the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, which was deployed in March 2014, are also investigating violations of human rights laws and international humanitarian laws.

In addition, the office of Ukraine’s prosecutor general has registered 65,000 allegations of Russian war crimes, identified hundreds of suspects, and begun court proceedings in more than 200 cases. The first concluded in May 2022, with the conviction of a Russian soldier for killing a civilian.

Also, last March Suella Braverman KC, then attorney general, appointed barrister Sir Howard Morrison KC as an independent adviser to Ukraine’s prosecutor general, Andriy Kostin. Since then, Morrison, who was a judge for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and for the ICC for 10 years, has been providing advice on investigating and prosecuting war crimes and overseeing a programme to train judges.

International criminal law operates at the frontiers of law and geopolitics, human rights and war. A relatively young area of practice, it originates in the international military tribunals held in Nuremberg and Tokyo after the second world war. That flurry of activity was followed by decades of relative silence and the discipline was kept alive in academia, says Wayne Jordash KC, barrister at Doughty Street Chambers.

The last 30 years have seen significant development in this field, Jordash says, with the creation of ad hoc international tribunals following the Yugoslavian civil war and the Rwandan genocide, and other ad hoc tribunals hearing trials of crimes allegedly committed in Sierra Leone, Cambodia, East Timor, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Lebanon. The ICC was created in 2002, following the adoption of the Rome Statute in 1998.

The crimes falling within the ambit of international criminal law are:

- genocide - the intentional destruction of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group;

- crimes against humanity - including murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, torture and rape, committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population; and

- war crimes – grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and violations of laws or customs of war.

To those who think that all war should be illegal, the idea that there are ‘laws for war’ may seem anathema. Jordash observes: ‘If you’re going to fight a war your aim is to defeat your enemy as quickly and effectively as possible, so why put constraints on it?’

Laws of war, Jordash says, are ‘nothing more than a nod to civilisation’, applying the generally accepted principle that those who are not directly involved in a war – civilians and prisoners of war – should not be targets. He accepts that there is an illogicality here, but he stresses that ‘it’s an important illogicality that seeks to spare the innocent’. Of course, he adds, some countries, such as Russia, take no notice of international laws and pursue strategies of total war.

Aside from their value to victims and the bereaved, Sir Geoffrey Nice KC says that war crimes trials serve two principal purposes: punishing those guilty of perpetrating war crimes, and deterring others from committing them.

But they perform another important function, which he suggests is ‘arguably [of] greatest value’, especially if the leaders are prosecuted – and prosecuted expeditiously. That is, says Nice, ‘they can set for all time the moral record’, stating who was in the right. This, he insists, is critical for the future of the countries concerned – and where the Bosnian trials failed.

Nice, who led the prosecution of former Serbian leader Slobodan Miloševic´ at the ICTY in The Hague, argues that it should be for Ukraine to deal with crimes committed by Russia. ‘It’s their right and their duty,’ he says, adding that there is ‘no great sense in having [other countries] involved’.

He accepts that gathering evidence against individual soldiers and proving their knowledge, state of mind and chain of command may well take decades. But he believes: ‘A trial of the leadership in a case like this is straightforward. There’s overwhelming evidence that Putin is guilty of war crimes.’

Nice further adds that trials should be held soon, otherwise Ukraine may suffer further, in particular by the ‘creeping development of arguments about moral equivalence of the warring parties, which extended trials can always allow, however unmerited’.

Although Ukraine’s laws permit trials to be held in absentia, Steven Kay KC, head of chambers at 9BR, says that as a head of state, Putin enjoys sovereign immunity from national prosecution under customary international law. And unless Russia loses the war and political change in the country follows, he suggests Russia will not deliver Putin up for trial.

The UK government is also supporting Ukraine’s investigations. Along with the United States and the European Union, it established the Atrocity Crimes Advisory Group ‘to provide strategic advice and operational assistance to Ukraine’s Office of the Prosecutor General’. The UK also funded a training programme for Ukrainian judges set to conduct trials for war crimes. A similar programme for Ukraine’s prosecutors, led by the Crown Prosecution Service, is due to start later this year.

Jordash lives in Ukraine, and since 2016 has been working with a team of 30 with his organisation, Global Rights Compliance, assisting Ukrainian prosecutors. While there has been an unprecedented international response to the conflict, Jordash says that much of this has amounted to mere rhetoric and does not translate to real assistance on the ground. More people are needed to help, he says, adding that it has been hard to get international criminal lawyers to come to Ukraine.

Some, he alleges, have got too used to sitting in The Hague and earning big UN salaries. ‘Getting up and working at national level to help beleaguered communities has been deprioritised,’ he laments.

The UK has also been backing the ICC’s efforts. In March, justice secretary Dominic Raab MP and Dilan Yes¸ilgöz-Zegerius, minister of justice and security of the Netherlands, will host a meeting to support the ICC’s investigations into alleged war crimes in Ukraine.

Announcing the meeting, Raab said: ‘Russian forces should know they cannot act with impunity and we will back Ukraine until justice is served.’ He also called on the international community to ‘give its strongest backing to the ICC’.

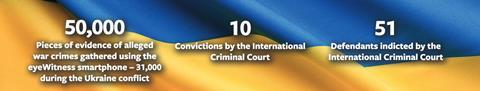

But the ICC’s track record gives cause for circumspection. In 20 years, it has spent billions of dollars but secured just 10 convictions (there have been four acquittals).

Gathering verifiable evidence

Evidence is key to any successful prosecution and smartphones make it easy for people to capture photographs and film of events. But such material can only be used in court cases if it can be verified.

In 2015, the International Bar Association (IBA) formed the eyeWitness to Atrocities organisation, which produced an app to help human rights defenders capture verifiable footage to submit in legal proceedings.

The eyeWitness app for Android smartphones captures photos, video and audio, and stamps the files with metadata which includes the time and date it was captured; the location and GPS coordinates where it was made; and whether the material was edited.

Users can upload files to eyeWitness’s secure server, which is hosted and protected by LexisNexis, for later verification and safe storage.

Evidence gathered using the eyeWitness app was used for the first time in 2018 to help secure two convictions at a military tribunal in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In 2012, two villages were attacked, looted and burnt to the ground by a unit of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), led by Gilbert Ndayambaje (alias Rafiki Castro) and Evariste Nizehimana (alias Kizito). Forty-eight people died.

Photographs captured in the aftermath of the attacks could not be verified, but five years later users of the eyeWitness app captured verifiable photographs and videos that helped corroborate the historical photos and witness testimony. These included photographs of mass graves, as well as of injuries of surviving victims. The embedded metadata confirmed the locations of the graves and villages.

The footage and metadata, along with witness statements and documentary evidence, were key to building the cases against Ndayambaje and Nizehimana, who were found guilty of murder and torture.

Since it was first launched, eyeWitness users have uploaded more than 50,000 pieces of footage from about 20 countries, more than 31,000 of them from Ukraine since February 2022.

‘Hamstrung’ justice

Even the ICC’s supporters, such as Jonathan Grimes, a solicitor at Kingsley Napley, accept that the court is ‘hamstrung’ by its structure and remit. Its jurisdiction only extends to its member states, he explains – and Russia is not a signatory. (Neither is the United States.)

The ICC has also struggled to act on cases involving signatories. In 2020, the ICC’s prosecutor closed a preliminary inquiry into allegations against UK soldiers who had served in Iraq, despite concluding that international crimes had been committed that met the court’s ‘gravity’ test. Though it is not within the purview of this article, the perceived illegality of the Iraq war and consequent failure of any forum to hold western leaders to account in its aftermath left many with jaundiced views of international criminal law enforcement.

Nice is concerned about the ICC’s failure to make any pronouncements about Putin’s responsibilities for war crimes, suggesting that the reason could be political – a notion that the court rebuts. He speculates that an eventual peace deal to end the Ukraine war might include an agreement that Putin does not face trial.

‘Putin and his senior commanders are guilty, beyond any reasonable doubt, of the crime of aggression – invading a UN member state other than in self-defence or for any lawful reason,’ says Geoffrey Robertson KC, the founding head of Doughty Street Chambers and a one-time appeal judge at the Special Court for Sierra Leone.

The ‘crime of aggression’ was added to the ICC’s jurisdiction in 2018, Robertson explains. However, states that have not ratified the Rome Statute, which established the ICC, or the statute’s amendments on the crime of aggression cannot be prosecuted for it without a referral from the United Nations Security Council.

As Russia is not a signatory to the ICC’s treaty and has a veto on the UN Security Council, Robertson believes the prospects of putting Putin in the dock there are minimal – unless, as with Miloševic´, he loses power and is sent to The Hague by a new Russian government.

Others have proposed the creation of a special criminal tribunal to support the ICC’s limited efforts.

'[International criminal law is] an industry where too many people make too much money and there is no incentive to cut through some of the inefficiencies'

Wayne Jordash KC, Doughty Street Chambers

The forums with the best track records of dealing with war crimes have been ad hoc tribunals, says Grimes. While imperfect, they have ‘got the job done’ and ‘commanded a grudging acceptance’ from the international legal community.

While these tribunals have worked well to create a more codified approach to the laws of war, according to Jordash, they have been less successful in securing ‘expeditious, fair and inexpensive’ trials.

Jordash represents Jovica Stanišic´, the former head of Serbia’s State Security Service, whose case before the ICTY has dragged on for 20 years. Stanišic´ is appealing a conviction for aiding and abetting crimes committed by Serb paramilitary groups in Šamac, Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Jordash’s view, international criminal law has ‘become an industry where too many people make too much money and there is no incentive to cut through some of the inefficiencies’.

The idea that the process of international justice must be ‘long and difficult’ must be challenged, insists Nice, because trials of leaders such as Putin can be swift and straightforward.

‘Lawyers and judges at formal courts earn their livings by operating slow-moving systems of one kind or another,’ he says, suggesting that they may find it harder than ‘regular non-lawyer citizens to appreciate the urgency of bringing to conclusions processes dealing with accountability for crimes in war’.

As an example of how tribunals can be conducted inexpensively, Nice points to the Independent Tribunal into Forced Organ Harvesting from Prisoners of Conscience in China (the China Tribunal) and the independent ‘Uyghur Tribunal’ relating to the alleged persecution and genocide of the Uyghur people in China. Nice chaired both tribunals, which were composed of pro bono members and senior staff, and ran for roughly a year each. Nice estimates that each cost under £300,000.

Whatever the forum, says Kay, who obtained the withdrawal of the ICC’s case against Uhuru Kenyatta, the former president of Kenya, for crimes against humanity, defence counsel in a war crimes trial should be well-resourced, protected and respected, and their essential role publicised by the court and the state.

Kay stresses that the outcome achieved in Kenyatta’s case would not have happened under the ICC’s legal aid defence budget. In addition, he argues, investigators, prosecutors and judges must be regularly reminded of their duties towards independence and impartiality to ensure that fair trial rights feature prominently.

Under the principle of universal jurisdiction, some offences, including certain war crimes and torture, can be prosecuted in the UK, even if the alleged acts occur elsewhere and may not involve the UK or a UK national.

Nevertheless, the UK does still require some kind of connection with the country, through citizenship, presence or residence, and it has attempted to exercise its powers in only a handful of cases.

Part of the reason for this, says Grimes, lies in the fact that the Metropolitan Police unit that investigates war crimes, SO15, is also the force’s Counter Terrorism Command, and with limited resources, the latter activity takes priority. He would like to see the functions split and the UK’s obligation to prosecute suspected war criminals to be ‘properly funded and have real priority’.

Overall, says Robertson, international law has developed quickly and worked ‘reasonably well to punish brutal leaders of states without powerful allies’. But he argues that the field is still in its ‘early days’, and realpolitik means there are limits to what it can achieve.

‘The great powers, notably Russia and the US, protect themselves and their friends,’ says Robertson, adding that the inaction over Putin ‘shows how weak the system is’.

Justice, argues Jordash, needs to be as close to the affected communities as possible. International justice and the ICC, he says, are a ‘last resort and should be treated as a failure of justice, not an adequate substitution’.

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist

2 Readers' comments