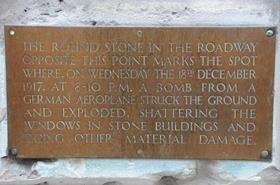

If you're ever walking down Chancery Lane with a few minutes to share, take a detour through Stone Buildings, the fine eighteenth century annex to Lincoln's Inn. On the wall of number 10, look out for a brass plaque. It indicates the spot where on 'Wednesday the 18th December 1917, at 8.10 PM, a bomb dropped from a German aeroplane struck the ground and exploded, shattering the windows in Stone Buildings and doing other material damage'.

As far as I can work out, the bomb was the first piece of hostile ordnance to hit UK legal professional premises in the two world wars*. The plaque was installed to remind passers-by of German 'frightfulness' in a world still shocked by such things. As it happened, the Gotha of the Imperial Air Service's England Squadron hit a legitimate target: number 10 is the headquarters of the Inns of Court Yeomanry, which at the time was running an Officers' Training Corps in a network of dummy trenches in Berkhamstead. But the military connection was sheer luck. Operating at the very extreme of its range, navigating by the gleam of the Thames in the moonlight, the bomber had done well to find London, let alone any specific address.

As such the bombing was a breach of international law: the 1907 Hague declaration prohibiting ‘the discharge of projectiles or explosives from balloons or by other new methods of a similar nature’. By 1917, of course, no one was paying much attention to such measures. England had been bombed since Christmas Eve 1914, when a German seaplane dropped two 2kg bombs on a vegetable patch outside Dover. London was attacked first by airships, then by twin-engined Gotha bombers and the astonishing multi-engined 'Giant', a biplane bigger than anything flown by the Germans in the next war. Sometimes with terrible consequences: in June 1917 a daylight raid killed 18 children at school in Poplar. Britain was retaliating in kind, randomly bombing any part of German-occupied territory our aircraft could reach. Indiscriminate strategic bombing had become a standard weapon of war.

For all this, I'm afraid my invariable reaction to the Stone Buildings plaque is open-mouthed admiration for the flyers. It was barely eight years since Louis Blériot made world headlines by coaxing a single-seat monoplane 20 miles across the English channel. The pilots of the England Squadron of the Luftstreitkräfte were operating at several times that distance, in the dark, in open-cockpit aircraft lacking flaps, trim-tabs or wheelbrakes, let alone the instrumentation mandatory for airworthiness in the most basic modern aircraft. No radio or parachutes, either. Perhaps most alarmingly to modern aviators, they took off with zero reserves of fuel into weather that could not be predicted much more than an hour ahead. A shift in the wind or an encounter with freezing cloud meant death.

The 18 December 1917 raid had a typical casualty rate. Oberleutnant Richard Walter led 15 Gothas and one Giant bomber from the squadron's base in Belgium, touching down just short of the coast to top up their fuel. Six aircraft reached London, prompting the speaker of the House of Commons to suspend sitting. High explosives and incendiary bombs caused damage valued at £225,000. One Gotha was shot down, seven others were lost to crashes and forced landings.

Despite the outrage at the Gotha raids, no one was prosecuted for indiscriminate bombing after the war. The Germans would have argued that the allied blockade of Germany killed far more innocent people than a few clumsily aimed bombs. More to the point, the British government had enthusiastically adopted the concept of strategic bombing and made it the raison d'etre of the new Royal Air Force.

Just off the other end of Chancery Lane, you can see memorials to the doctrine's apotheosis. Opposite the Royal Courts of Justice, the stonework of St Clement Danes still shows the pockmarks of the 1940 Blitz. And outside the main portal stands the statue of the man who led the RAF's response, Arthur 'Bomber' Harris. The 1992 sculpture catches a puff-chested truculant Harris standing at ease, gazing with what looks like contempt towards the Westminster politicians whose dirty work he did. Harris is not an immediately sympathetic character; biographers have labelled him at best arrogant and cold-hearted, at worst a mass murderer. But he was also a brave man who shouldered responsibility and never minced words about what he was doing - killing Germans, at the time when that was the only practical way of attacking the Nazi tyranny. Millions of words have been written about the bombing campaign (a good start is AC Grayling's Among the Dead Cities) but in the end all that needs to be said is that, while the offensive failed in military terms, it kept the western democracies in the war. We walk in freedom - many of us walk at all - as a result.

And, childish as it might sound, it must be repeated that the other lot started it. 'They sowed the wind, now they are going to reap the whirlwind,' Harris memorably quoted from the Old Testament. By the time his whirlwind had passed, the idea of putting up a plaque to commemorate a few broken windows would seem very quaint indeed.

*I seem to be wrong about this - see the comments below.

6 Readers' comments