I was reminded this week of a scene from the 1982 film ‘Gandhi’, directed by Richard Attenborough.

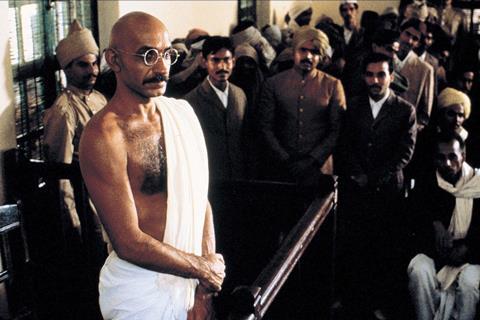

In it, Gandhi (Ben Kingsley, pictured below) is brought to court. As he enters, the judge, Justice Robert Stonehouse Broomfield (Trevor Howard), stands in respect, and the whole court therefore has to stand, too. The script says that when the eyes of Gandhi and the judge meet, the judge gives him a little bow.

Gandhi represents himself and pleads guilty. The judge announces that he is obliged to sentence him to six years in prison, but adds the words:

‘If however His Majesty's Government could – at some later date – see fit to reduce that term, no one would be better pleased than I.’

Judge Broomfield was a real person, a barrister in the Indian Civil Service, and a Puisne Judge of the High Court of Judicature at Bombay. I can find no trace of whether he said similar words in real life.

But an equivalent scene did occur last week at Wolverhampton Magistrates' Court, although some of the exact words of the District Judge (District Judge Wilkinson) are contested.

Just as Gandhi was a highly controversial figure in his lifetime, so were the defendants in Wolverhampton.

Ghandi is and was considered the equivalent of a saint by many, but Churchill loathed him, doubted his authenticity and famously called him ‘a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Viceregal palace’.

Similarly, the defendants in the magistrates court last week provoke either great fury or respect. They were Just Stop Oil activists, who had been trying to halt the distribution of oil from the Esso Fuel Terminal in Birmingham in April 2022.

According to Just Stop Oil’s account, District Judge Wilkinson said:

‘It’s abundantly clear that you are all good people. You are intelligent, articulate and a pleasure to deal with. It’s unarguable that man-made global warming is real and we are facing a climate [crisis]. Your aims are admirable and it is accepted by me and the Crown Prosecution Service that your views are reasonable and genuinely held. Your fears are ably and genuinely articulated and are supported by the science.

When the United Nations Secretary General gives a speech saying that the activity of fossil fuel companies is incompatible with human survival, we should all be very aware of the need for change …

[No one can therefore criticise your motivations and indeed each of you has spoken individually about your own personal experiences, motivations and actions. Many of your explanations for your actions were deeply emotive and I am sure all listening were moved by them. I know I was.]

Thank you for opening my eyes to certain things. Most, I was acutely and depressingly aware of, but there were certain things.

I say this and I mean this sadly, I have to convict you. You are good people and I will not issue a punitive sentence. Your arrests and loss of good character are sufficient. Good people doing the wrong thing cannot make the wrong thing right. I don’t say this, ever, but it has been a pleasure dealing with you.’

Those found guilty were ordered to pay costs of either £250 or £500. All were sentenced to a 12 month conditional discharge and made to pay a £22 surcharge.

After Just Stop Oil publicised the judge’s remarks, the Judicial Office, which represents judges, took the unusual step of admonishing the group for allegedly misquoting the judge. Since the words were taken down contemporaneously, not everything was accurate. I have not seen the original judgment, and, therefore, part of the above text reflects corrections made by Just Stop Oil, and the parts in square brackets are my understanding of what the Judicial Office wanted corrected.

The confrontation between climate activists and the state is now shifting to the courts. There are reports that some courts do not allow climate activists to mention the reason for their action, on the grounds that it is immaterial to the consequences. On the other hand, Extinction Rebellion has provided information on several other cases where a judge has expressed sympathy for the defendants’ cause.

It becomes an interesting state of affairs if judges – all in the lower criminal courts, true - are no longer reliable instruments for implementing the law wholeheartedly on behalf of the state. If the trend increases, the law itself is called into question, which is doubtless the aim of the activists.

This is one of the ways in which the climate crisis is impacting the legal system.

The message from the Gandhi film was that the state had its own doubts about the Raj – and the Raj ended 25 years later. The climate crisis meanwhile will only get worse.

Jonathan Goldsmith is Law Society Council member for EU & International, chair of the Law Society’s Policy & Regulatory Affairs Committee and a member of its board. All views expressed are personal and are not made in his capacity as a Law Society Council member, nor on behalf of the Law Society

This article is now closed for comment.

5 Readers' comments