It had been a long day in court. But, putting away his black cap, Sir Alexander Cockburn ruled at 5pm that there was still time to swear in a jury to deal with an ugly spat between two public figures.

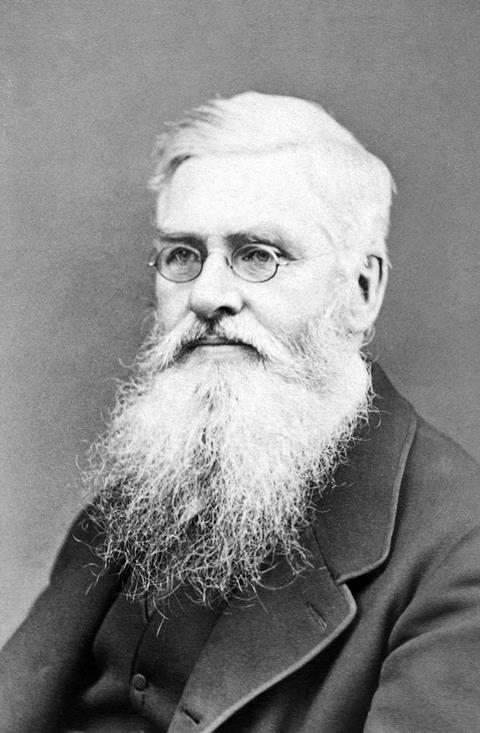

The claimant that Saturday in Chelmsford Shire Hall was the renowned self-taught naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, whose discoveries had prompted Charles Darwin to publish his Origin of Species in 1859. Wallace's target: John Hampden, author of Shewing the World to be a Stationary Plane and not a Revolving Globe.

The subject of their antagonism? Fallout from a £500 wager over an experiment to test Hampden's contention that the earth is flat.

Contrary to popular myth, belief in a flat earth is a modern phenomenon. Certainly Columbus never feared sailing over any edge: in 1492, astronomers and mariners had known for a millennium that the earth must be spherical. The third century BCE scholar Eratosthenes even had a reasonably accurate stab at measuring its circumference. Globism survived the so-called 'dark ages'; few scholars found any incompatability between a spherical earth (albeit at the centre of the Universe) and Biblical 'truth'.

It took the eminently practical Victorians to revive flat earthism. This wasn't so much a revolt against a technological age as a consequence of it. At a time when knowledge paradigms (though the phrase was not yet in use) were being overturned left, right and centre, the opportunity was ripe for enterprising autodidacts to make names for themselves through the new social media of the penny post, cheap periodicals and self-improvement societies.

So-called 'zetetic astronomy' was driven, at least ostensibly, by the spirit of scientific enquiry. Its promoters found an ideal site for experimental proof: the Old Bedford River in Cambridgeshire, dug as part of a fenland drainage scheme, runs dead straight and level for more than six miles. If the earth is flat, an observer at water level equipped with a suitable telescope should be able to see a target also at water level six miles away. If the earth is a globe, the target will be obscured by a horizon rising less than halfway.

As a riposte to the scientific establishment's rejection of his ideas, Hampden made a public wager: betting £500 (something like £75,000 today) that he could demonstrate the flatness of the earth. Cash-strapped Wallace - who, unlike his friend Darwin had no private income - took him up on the offer, confident from his experience as a surveyor and a world voyager, that he could shut the debate down for good. In March 1870, accompanied by umpires, the parties met on Welney Bridge.

While the experiment went anything but smoothly, the neutral referee John Walsh, who was holding both parties' stakes in escrow, pronounced Wallace the winner.

However any hope that the experiment would change flat earthers' minds was in vain. (The definitive Bedford Levels experiment, producing photographic proof of the earth's curvature at the spot, was carried out only in 1901.) Hampden redoubled his campaign, publicly accusing Wallace and other figures including the astronomer royal of conspiracy and fraud. In a letter to Wallace's pregnant wife Annie, he wrote: 'Madam, if your infernal thief of a husband is brought home some day in a hurdle, with every bone in his head smashed to pulp, you will know the reason.'

Wallace turned to the law. Hampden was arrested, charged with threatening to kill, and fined £100. Shortly afterwards, a libel jury awarded Wallace £600 in damages; Hampden pleaded bankrupcty. The following year Hampden was back in the dock at Bow Street facing an action by Walsh; later that year he was committed to trial at the Old Bailey and committed to Newgate Prison. In January 1875, Wallace received the latest in a series of defamatory postcards. It was that which led to the trial at the Essex Assizes.

The Chelmsford Recorder's account of proceedings suggests that the lord chief justice was unimpressed with Hampden's attempt to justify his defamations as true. Told the burden of doing so lay upon him, Hampden said only: 'Well I am sure, my lord, my hands are tied.'

'I wish they had been tied when you wrote these letters,' Cockburn retorted, to laughter in court. 'His lordship added that there had been nothing adduced to show that Mr. Wallace was in any sense of the term either a swindler or a thief, and there was nothing whatever against his character; and there was no alternative but for the jury to find a verdict of guilty.'

The jury obliged. 'Mr. Hampden, this must be put a stop to,' his lordship pronounced. 'The sentence upon you is, that you be imprisoned for 12 months, and that at the end of that period you find sureties ... for your good behaviour for two years. I will put a stop to this libelling.'

Hampden was conducted to the cells. 'The court rose shortly after six o’clock until eleven am on Monday,' the newspaper recorded.

Incredibly, that was not the end of Hampden's dealings with the courts. The following year in Hampden v Walsh the High Court ruled that the agreement to pay £500 had been a wager and thus legally unenforceable: on top of the return of his stake, Hampden was awarded £200 costs from Walsh. Wallace, honourably, coughed up.

Hampden wasn't in court as he was still in Chelmsford Gaol, where he served nine months. There, his daily routine would have been interrupted by the outcome of the main event of the Assizes, the execution of Richard Coates for the murder of six-year-old Alice Boughen, barely two weeks after the lord chief justice had pronounced sentence.

Hampden himself died in 1891. In its death notice, the Daily Graphic recalled that he had once prophesied that 'some startling events' would occur in that year. 'Very likely he was right in this somewhat vague anticipation,' the paper observed.

More than a century on, flat earth believers are still around; nowadays of course disseminating their repudiations online rather than in public meetings. (Algorithms seem to have identified me from my search history as a potential convert.) Among modern disciples there seems to be an overlap with Moon landing deniers, who seem to be enjoying a renaissance, and of course with religious fundamentalists.

Hampden's spirit survives in many a crank conspiracist litigant in person, some of whose emails I'm copied into every week.

Wallace, a largely unsung hero of science, lived to the grand age of 90, dying in 1913. In his autobiography, he referred to his involvement with flat-earthers as 'the most regrettable incident of my life'. If he recorded his thoughts on the legal system, I would love to know them.

Further reading: Flat Earth, the History of an Infamous Idea, Christine Garwood, Pan 2007

3 Readers' comments