In September 1939, John Noel Isaac was a young man with a brilliant future in the law. The Jesus College, Oxford, graduate had made the partnership of City firm Clifford-Turner & Co only four years after qualification. He specialised in company matters at the firm’s office at 11 Old Jewry, off Cheapside in the City of London.

While no doubt a diligent company lawyer, Isaac's real passion was for flying. In January 1939 he was commissioned into the Royal Air Force as a part-time reservist under a scheme set up in 1925 to create a throughput of pilots who would not want employment as senior officers. At the outset, much emphasis was placed on securing the 'right sort of chap': for a start, recruits had to hold a private pilot's licence and have either a private income or an understanding employer. Isaac's unit, 600 Squadron based at Hendon Aerodrome in North London, wasn't quite as exclusive as its rival 601, the 'millionaires' squadron', but it nonetheless boasted an aristocrat, the Viscount Carlow, as commanding officer.

However any suggestion that 600 Sqdn was merely a sporting club for privileged boy racers would be unfair. Its backbone was a highly professional cadre of ground and technical crews, in 1939 preparing grimly to defend London from what everyone expected to be a Guernica-style aerial assault. At the time Isaac joined, 600 Sqdn was equipping with a very serious aircraft, the Bristol Blenheim twin engined all-metal fighter-bomber. While later experience would show the Blenheim to be hopelessly outclassed as a day fighter, at the time it was considered to be the state of the art.

It was also a very considerable step up in complexity from the Tiger Moth and Avro Tutor biplanes in which the volunteer reservists would have first learned to fly.

Only one Blenheim is airworthy today, and it is interesting to read modern professional pilots' assessments. Two points that stand out are the awkwardness of the cockpit hatch and the 'all over the place' arrangement of the controls and instruments. The levers to adjust the propeller blades' pitch, for example, are behind the pilot's seat - alongside the carburettor cut-out levers.

When an engine fails in a twin-engined propeller aircraft, it will 'windmill', creating a massive one-sided air-brake. The pilot must instantly counteract this with aileron and rudder, while stopping the dead engine from spinning with the pitch control. Any error will cause a fatal stall.

At 1250 on Sunday 3 September 1939, the Blenheim in which PO Isaac was carrying out a solo practice flight stalled on approach to Hendon aerodrome and plunged into a residential street. There was no way out for the pilot: an ejection seat might have saved Isaac, but that technology, along with the mindset that pilots' lives are worth the extra weight and expense, lay 10 years and many, many, aircrew deaths in the future.

Britain had been at war for precisely one hour and 50 minutes. To the good citizens of Hendon, even though accustomed to aviation and its mishaps, the crash may have sounded like the opening of an airborne armageddon.

A wartime hush-up immediately descended - presumably the powers that be didn't want the public to dwell on the fact that RAF aircraft could fall out of the sky without a shot being fired. Isaac's body, or what was left of it, was cremated at Golders Green where, a few years ago, I spotted his memorial near plaques for Larry Adler, Marc Bolan and Keith Moon, along with a more appropriate musical neighbour, Eric Coates, composer of The Dam Busters theme.

Someone, presumably at Clifford Turner, took the trouble to notify the Law Society's Gazette, then a monthly publication. In our November 1939 edition Isaac's name, along with that of Pilot Officer Richard Bowyer (another training crash, on 18 September), re-inaugurates the 'Roll of Honour' column which had filled so many pages a generation before.

Isaac's squadron went on to serve with distinction throughout the war, in the Battle of Britain, North Africa, Malta and Italy. It was disbanded in 1957 but reformed in 1999 as a headquarters support squadron. It is still active today, based at RAF Northholt, where its roles include legal support.

Clifford Turner would in 1987 become one half of global giant Clifford Chance. Isaac gets a paragraph in the firm's official history, which also records that the Old Jewry office was damaged by a flying bomb in October 1944.

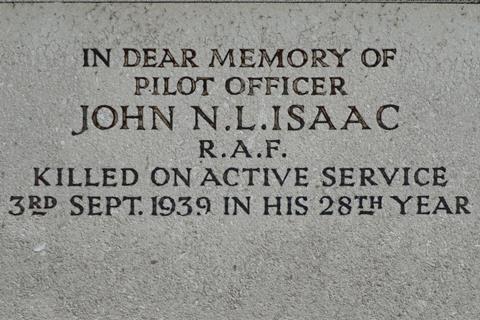

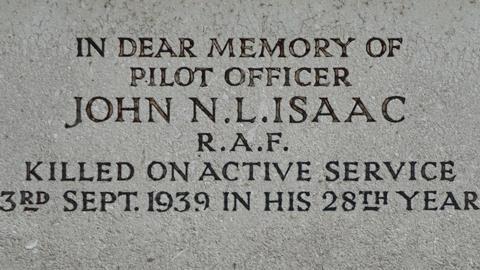

In the greater history, PO Isaac became a footnote to a footnote: he is now reckoned to be the first Briton to die on active service in the war. Perhaps that distinction dignifies a tragic, probably unnecessary, accident. An accident which, if it happened today, would no doubt trigger critical scrutiny of the design of the Bristol Blenheim, the adequacy of the RAF's training regime and the wisdom of conducting it over built-up areas. Not to mention legal action.

But Britain 80 years ago was evidently a different place. Just as well, really. I'd rather think of John Noel Laughton Isaac not as a 'victim' but as a conscientious and intelligent patriot, who, on 3 September 1939, could see the perils ahead and did not flinch. His name deserves its place of honour.

6 Readers' comments