Lay magistrates should lose the power to pass custodial sentences, the Howard League for Penal Reform told David Gauke’s independent sentencing review last week.

If that sounds somewhat unrealistic, remember that the former Conservative justice secretary had encouraged people to send him proposals that were ambitious or challenged current thinking. An identical request was made by Sir Brian Leveson, who is conducting an independent review of the criminal courts. But magistrates’ powers to imprison offenders for up to 12 months have only recently been restored and I doubt if either reviewer will advise the justice secretary Shabana Mahmood, whose officials will already be working on the outlines of the next criminal justice bill, that imprisonment should solely be the responsibility of paid judges.

Much the same effect could be achieved, though, if Mahmood accepts a related recommendation. It would involve abolishing the use of short prison sentences. The Howard League says there is a ‘wealth of evidence, including the Ministry of Justice’s own research, which suggests that short sentences of 12 months or less are ineffective and harmful’. Those released from sentences of up to a year are more likely than not to reoffend.

The Magistrates’ Association, in its response to Gauke, accepts that short custodial sentences – which it defines as six months or less – ‘are counter-productive for many offenders and offences, due to their disruptive impact on a person’s life and the limited potential for rehabilitation’. But it wants to keep them as a last resort, maintaining confidence in the criminal justice system and protecting the public where no viable community alternative exists.

The only surefire way of stopping the prisons from running out of space again is to reverse what the Howard League calls sentence inflation. It wants to reset the clock, returning to the sentencing benchmarks of the 1990s. But a former politician like Gauke might baulk at a reform that would look like going soft on crime. And Lord Justice William Davis, who chairs the Sentencing Council, told me in a podcast interview last year that reducing all sentences by, say, 10% would be ‘a very crude weapon indeed’.

So Mahmood will be relying on Leveson to recommend ways of diverting offenders away from the criminal justice system. The former head of criminal justice is accepting submissions until the end of this month.

But there is not much Leveson doesn’t already know about criminal justice. In a report published exactly 10 years ago, he identified a number of possible statutory reforms. These drew on recommendations made by Lord Justice Auld in 2001. And Leveson will also recall the Roskill committee’s majority recommendation in 1986 – never implemented – that defendants in complex fraud cases should be tried by a judge sitting with two ‘handpicked’ lay members.

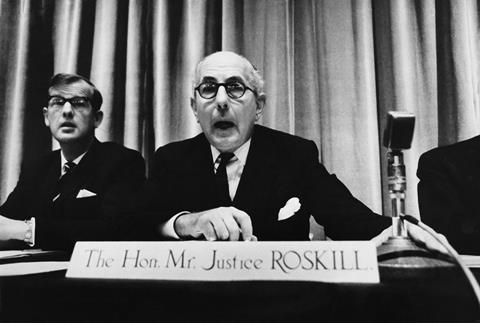

Roskill (pictured) was concerned about an increase in the number of fraud trials taking four weeks or more – which in those far-off days seemed a long time. ‘We do not believe that in a serious fraud trial of, say, 20 working days,’ his committee said, ‘the average juror can retain in his memory all the essential facts and figures on which his verdict should ultimately depend.’

Roskill’s recommendation was picked up by Auld. ‘As an alternative to trial by judge and jury in serious and complex fraud cases,’ he recommended, ‘the nominated trial judge should be empowered to direct trial by himself sitting with lay members or, where the defendant has opted for trial by judge alone, by himself alone.’ Leveson seemed to favour the idea in 2015, observing that ‘the very real expense of exceptionally long trials would be reduced if judges (with assessors) conducted these trials’.

But Auld’s report is best remembered for recommending that the Crown and magistrates’ courts should be merged into a unified criminal court, with a new middle tier to hear cases that are currently tried either by magistrates or by judge and jury. Crucially, this intermediate court would comprise a professional judge and two lay magistrates, meaning that defendants facing ‘either-way’ charges would lose the right to insist on a jury trial.

And that idea has already been supported by the justice minister Sarah Sackman KC. ‘Jury trials will always be there for the most serious offences,’ she said last Sunday. ‘But we have to countenance the notion that certain offences will come out of the Crown court altogether and that some offences might be more appropriate for not having a jury trial but for having a judge-led trial.’

In its election manifesto, Labour said it would ‘carry out a review of sentencing to ensure it is brought up to date’. In context, that was meant to sound tough. But a much better way of bringing sentencing up to date would be to restore the best ideas of the past.

joshua@rozenberg.net

2 Readers' comments