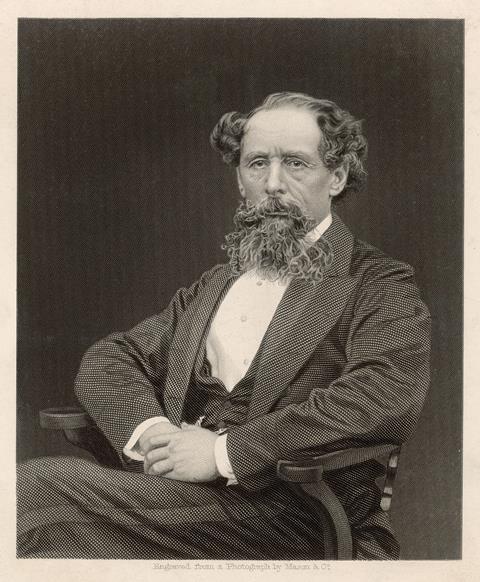

Recent parliamentary events have led me to long for a new Charles Dickens to bring alive the extremes of our legal system.

At one end, there are the crammed prisons and criminals released early, closed courts, trials delayed for years, and legal aid solicitors on the brink of a nervous breakdown trying to make ends meet. We read about these all the time. The lord chancellor recently took small steps to try and improve the position of some criminal legal aid solicitors (police station and youth court work, and reimbursement for travel time for solicitors who work or commute to work in areas with fewer than two legal aid providers, as well as the Isle of Wight).

At the other end, there are the large fees highlighted this month during a session of the Commons Business and Trade Committee on the Post Office Horizon scandal’s redress scheme. Even allowing for political grandstanding, the exchanges contrast strongly with the scenes of poverty highlighted above.

The chair of the committee, Liam Byrne, clearly enjoyed the shock he could express at the sums lawyers were charging, contrasting them with the fate of the subpostmasters still awaiting payouts: ‘The challenge we have is that when we look at the compensation number that has gone out the door, it is about £470m. When we look at the total legal cost, it is about £270m. So as of now, it is costing a fortune to get the redress payments to subpostmasters.’

It emerged that Herbert Smith Freehills had billed £51m for settling 2,450 cases, meaning a fee of £21,000 per case, or so said the chair. The law firm argued that the fees included the cost of setting up the scheme in the first place. But the chair would not let go: ‘Despite all the set-up costs, is £21,000 a case reasonable for taxpayers to pay?’

Herbert Smith Freehills said yes. Other law firms present were given similar treatment.

This was not the only instance of legal costs recently raised in parliament. There was also a debate about strategic litigation against public participation (SLAPPs).

Joe Powell, the Labour MP for Kensington and Chelsea, noted that when Catherine Belton’s book Putin’s People was published, several Russian oligarchs and a Russian state oil company launched lawsuits. The action by Roman Abramovich was settled ‘but had that trial gone ahead, the legal bill would likely have exceeded £10m’.

He also noted that Tom Burgis faced legal action for his book Kleptopia. Had that case gone to trial and been lost, the estimated costs, including the claimant’s legal fees and damages, would have been £1.5m.

A great deal of the power of SLAPPs comes from the fact that the legal costs are so punishingly high that civil society is chilled into silence. But need it be that way? I have written before how a defamation action in the Italian courts costs 50-100 times less than in the UK – £25,000 is much less intimidating than £2.5m, and so at least some of the sting of a SLAPP action is diminished.

The cost of legal services is an issue for the profession. It is used by our international competitors to lure clients towards their own national law and court system. We treat legal costs as an immutable fact, like the sky and the clouds, but the existence of cheaper legal systems shows that there must be another way.

Of course, the economics are complex – so complex that inertia is the most appealing solution. That is why we need another Dickens. We need a powerful story which will awaken those responsible into action. This Dickens story will have a legal aid lawyer who is not paid two-thirds of their fee because it falls between the amount of the fixed fee and the amount of the escape clause, and who has to reduce office space because of lack of funds and is put on anti-depressants. And it will have another lawyer who bills well over £1,000 per hour, with the working environment and lifestyle that go with such sums.

It is great that we have successful lawyers who can command high fees because of their expertise. Our legal profession is world-leading and contributes substantially to the UK economy (£34bn – or 1.6% – of gross value added in 2022).

But our lawyers should not be viewed in isolated categories. Fee levels have consequences, both the low fees in legal aid and the high fees commanded by others. If we do not acknowledge these consequences and ponder them, others may do so for us.

Jonathan Goldsmith is Law Society Council member for EU & International, chair of the Law Society’s Policy & Regulatory Affairs Committee and a member of its board. All views expressed are personal and are not made in his capacity as a Law Society Council member, nor on behalf of the Law Society

7 Readers' comments