Once upon a time the traveller from Athens to Eleusis was at risk of capture by a B&B proprietor with marked anti-social tendencies. If you were too long for his bed, he would cut you down to size. If too short, he would stretch you out on his do-it-yourself home body rack.

Over the last 15 years I was often reminded of Procrustes as I watched successive governments try to control legal aid expenditure. The rack was never needed. The axe – or the saw - was in constant use, but never with any sensible over-arching plan. The Labour government nibbled away at the edges as 30 consultation papers fluttered around. The coalition government preferred old-fashioned butchery. The 25% cuts it inflicted at one fell swoop were dictated by a political priority that left justice among the also rans. I spent the eighth decade of my life comforting the walking wounded.

This is why I was pleased to accept Lord Bach’s invitation to join his commission on access to justice. Although the Labour party was sponsoring this enterprise, he said that he wanted us to go back to first principles, to study the problems in depth, and to come up with solutions that might appeal across the political spectrum. Justice was too precious to be the plaything of the party game.

Now, two years later, what have we achieved? We have assembled – and published today - a detailed body of evidence that will leave those who are interested in these things drooling with delight for years to come. The task of organising this material was largely left to me. The analysis which forms an appendix to our report provides the factual underpinnings for the stark messages the report contains. Another appendix tells the story of the first 70 years of legal aid.

The report itself falls into two parts, one visionary, the other down to earth. In the visionary bit we propose that everyone subject to our laws should have a statutory right to justice, and we explain what this means. And with lord chancellors and legal aid ministers following each other to the exit door in rapid succession – there have been five of each since 2012 – we propose a new justice commission, probably headed by a very senior judge or ex-judge, to be the future guardians of the people’s new statutory right.

In part two we identify those areas, particularly in the field of public legal education and early legal help, which call for action at an early date. Far more use should be made of modern technology, but not at the expense of face to face advice when this is needed. We remind ourselves that in today’s prices the government is now underspending half a billion pounds a year against their budget when the cuts were made. And we recall that every reputable cost-benefit analysis we have ever seen shows that money spent on early legal help much more than pays its way in terms of future economic benefits for the exchequer. If you know your rights, you are less likely to succumb to ill-health, problems at work, or relationship breakdown, with all the costs they involve. Ideally, a legal aid lawyer should be part of the team on call at every general practitioner’s clinic.

The cuts have been greatest in family law. Judges despair of achieving justice when the parties so often lack sensible professional help. A small amount of early legal help at the time of relationship breakdown is vital: it will lead to many more mediated solutions, as opposed to arms’ length battles between litigants in person. We also suggest six ways of improving things: legal representation when the primary care of a child is in dispute, or when there is an application to remove a child from the jurisdiction, for instance. We also envisage the new commission drawing up a flexible code, which it can alter as time goes on without having to wait endlessly for primary legislation to alter it.

But we cannot think of everything, and while we expose the inadequacy of the exceptional case funding scheme, we show how the new right of access to justice may lead to a judge certifying that a grant of legal aid is necessary in the interests of justice. And if this certificate does not bear fruit, judicial review may lie against the new, independent body that will be running the legal aid scheme at arm’s length from government.

There will be plenty to discuss. This is an outline design, not a blueprint. Everyone recognises that there were faults in the earlier regimes, and some of these faults unscrupulous lawyers were not slow to exploit. In every opinion poll, however, the consumer votes for justice, and our proposals put the interests of the consumer first.

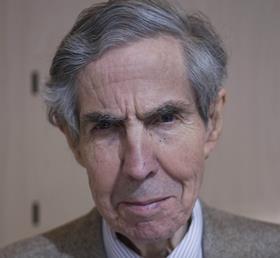

Sir Henry Brooke CMG is a retired Lord Justice of Appeal. He writes a regular blog

Justice stalwart Sir Henry Brooke dies at 81

Tributes are pouring in from the profession after the retired judge passed away following heart surgery.

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Justice is too precious for political football

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

No comments yet