On the last two days of this month, an unlisted tribunal is planning to sit at an undisclosed location. Its four unnamed members include a Court of Appeal judge, a High Court judge (in each case, either serving or former) and two non-lawyers. The panel will consider allegations that have not been published and make findings of fact that will not be revealed.

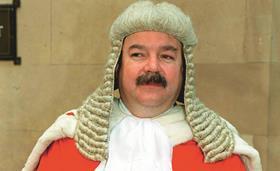

The only thing we know for sure is the name of the individual whose conduct this disciplinary panel is investigating. He is the senior judge of the High Court Chancery Division, Sir Peter Winston Smith.

It is more 10 years since I first called for Mr Justice Peter Smith’s resignation. But this piece is not about the misconduct allegations he faces. It is about the failure of the statutory disciplinary process to deal with those allegations in a timely and transparent manner.

Of course, judicial independence means that judges must be insulated against ill-founded complaints by aggrieved litigants. Disciplinary matters in most walks of life are dealt with in private. But these are allegations against a High Court judge who agreed not to sit while they were investigated. Smith has effectively been suspended on full pay since May 2016.

Officials from the Judicial Conduct Investigations Office (JCIO) began investigating Smith’s conduct in July 2015. That was when he was trying a case against British Airways and asked the airline’s counsel, again and again, why his personal luggage had not arrived after a holiday flight. He also emailed BA’s chairman. I suspect the allegation is what the JCIO calls ‘misusing judicial status for personal gain or advantage’. But that, like so much, has never been confirmed.

Later in 2015, a judge was appointed to advise the lord chief justice and lord chancellor on the complaint. Smith responded early in 2016. The rules say that if a nominated judge recommends removal or suspension from office, the office-holder can insist that the complaint is referred to a disciplinary panel. Such a panel first met last year.

But then, in the spring of 2016, the JCIO began a new investigation – into what senior judges called a ‘shocking’ and ‘disgraceful’ letter that the judge had written in response to a newspaper article by Lord Pannick QC. Smith told Pannick’s chambers that he would no longer support their applications for QC status. The Court of Appeal, which published the letter, said it showed ‘a deeply worrying and fundamental lack of understanding of the proper role of a judge’.

The disciplinary panel was due to meet for the second time in March this year but failed to do so – for reasons that were not disclosed. Media reports mentioned health problems. I speculated at the time that Smith would retire in May when he reached 65 and qualified for a 15-year judicial pension. He did not.

This month’s hearing is expected to hear from Smith’s lawyers and take oral evidence. Under the rules, panel members must draft a report setting out the facts of the case. They must say whether they think Smith is guilty of misconduct and what disciplinary action, if any, they think should be taken against him.

Smith then has 10 days to comment on the draft. The panel must ‘have regard to’ his comments before finalising its report to the lord chief justice and lord chancellor. That will surely take us into next year. If Smith has grounds, he may then apply for judicial review.

On its website, the JCIO promises that anyone who complains about a judge will be given a progress update ‘every four weeks (unless clearly stated otherwise)’. Under the judicial conduct rules, a disciplinary panel may disclose a summary of its draft report to the complainant, omitting any confidential information.

Any complainant who disclosed that summary to a reporter would risk being sued for breach of statutory duty – if Smith could identify the reporter’s source. But that may be a chance the complainant would be willing to take.

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 says that ‘information as to disciplinary action’ may be disclosed with the agreement of the lord chancellor and the lord chief justice. Regulations confirm that they may ‘agree to the publication of information about disciplinary proceedings or the taking of disciplinary action’.

So Sir Ian Burnett, who will be sworn in today as lord chief justice, should demonstrate his commitment to greater openness by seeking David Lidington’s approval to name the panel members and outline the allegations they will consider.

At the very least, Burnett and Lidington should confirm that a summary of the panel’s draft report will be published at the same time as it is sent to complainants. Updates on cases of this seriousness should not be a privilege for those who choose to complain. Open justice demands nothing less.

joshua@rozenberg.net

2 Readers' comments