This week, Britain stands on the cusp of change. Whether or not Theresa May wins the election on Thursday, we can reasonably expect the prime minister to replace Elizabeth Truss with someone better suited to the role of lord chancellor and secretary of state for justice. For May to appoint a lawyer would be an admission that she got it wrong last year. I would therefore expect the job to go to a minister with no legal qualifications – someone like Justine Greening, for example. But whoever occupies this demanding post will face a number of urgent challenges.

Of these, the most immediate is to ensure that a new lord chief justice is appointed in good time to succeed Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd at the beginning of October. A panel set up by the Judicial Appointments Commission is expecting to interview candidates this month. The lord chancellor can accept or – with written reasons – reject its recommendation but cannot choose an alternative.

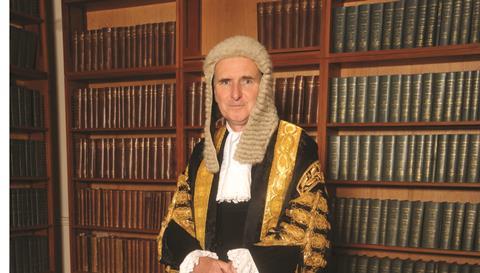

It would be fascinating to know whether the panel’s choice will be influenced by the perceived preferences of the sitting lord chancellor. We know that Truss insisted that the next chief justice of England and Wales should be able to serve for at least four years – thereby excluding Sir Brian Leveson and Lady Justice Hallett, who must retire at the age of 70 in 2019. But what we do not know is whether Truss asked the panel to favour, say, IT skills over diversity. There is no obvious candidate but Lord Justice Lloyd Jones, 65, now seems to be the favourite.

An early announcement is needed not only because the new chief justice will not have served as one of Thomas’s two effective deputies and so will need more time to prepare. Some of the candidates for chief justice may also have applied for one of three vacancies in the UK Supreme Court and Lady Hale, who is expected to succeed Lord Neuberger as president, will need to know who is available.

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing the incoming chief justice is the likely shortage of judges. It should be possible to find six good candidates for gaps in the Court of Appeal. But promotions will leave up to 25 empty places in the High Court – some of which, on past experience, it will be impossible to fill. A few judges may be promoted from the circuit bench but that will merely make it harder to fill the unprecedented and implausibly precise ‘116.5 vacancies’ in the Crown and county courts.

So the lord chancellor should seek to put the judicial retirement age back up to 75. That limit still applies to the small handful of serving judges who joined the bench before the rules were changed in April 1995. The best known of these is Hale who, as a vigorous and busy 72-year-old, certainly lives up to her name.

Neuberger, who has never quite said he is retiring to make way for an older woman, told The Times last week that an increased retirement age might result in ‘judges having to be told to retire early slightly more often’. But, he added, ‘that would be a very small price for avoiding the huge loss of experience and talent attributable to the current statutory retirement age’. He makes a good case – but it would be more convincing if merely telling a bad judge to retire early was not so demonstrably ineffective.

A strong and independent judiciary is fundamental to the quality and effectiveness of our judicial system. The judges also have a vital role to play in ensuring that the forthcoming Brexit legislation achieves its aim. And they need the full support of the lord chancellor. But the holder of this great office also faces other challenges.

One is to ensure that the Prisons and Courts Bill, which lapsed when parliament was dissolved, is back in the Queen’s speech on 19 June. That should not be too difficult: the Conservatives’ manifesto contained promises to ‘create a new legal framework for prisons’ and ‘modernise our courts’. I know that some solicitors worry that online courts will put them out of a job. But if more defendants can plead guilty online – and if more litigants are able to sue and defend claims on their smartphones – then more clients will need legal advice at key stages from agile and adaptable lawyers.

One more challenge for the lord chancellor is to thwart the prime minister’s plan to incorporate the Serious Fraud Office into the National Crime Agency. Abolishing this unique joint fraud investigator and prosecutor has long been May’s ambition. But she will have to do a great deal more to convince her growing list of critics that breaking up a body which generates huge fines for the exchequer is really in the public interest.

6 Readers' comments